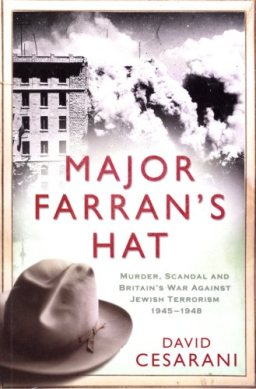

Major Farran’s Hat: Murder, Scandal and Britain’s War Against Jewish Terrorism 1945-1948

David Cesarani

London: William Heinemann, 2009, h/b, £20

On 6 May 1947 a British undercover squad, under the command of Major Roy Farran, picked up sixteen-year-old Alexander Rubowitz, a young Zionist activist. He was taken away for ‘interrogation’. After an hour of questioning, Farran beat him to death with a rock. The boy’s body was stripped naked, mutilated and left for the jackals. Incredibly, when capturing Rubowitz, Farran had lost his hat with the letters FARAN or perhaps FARKAN clearly legible! The boy’s disappearance was to become a major scandal in the closing days of British colonial rule in Palestine. While the outline of the story has been known for some time, David Cesarani’s new book, Major Farran’s Hat, provides as detailed and comprehensive an account of the episode as we are ever likely to get. That such an account is necessary was demonstrated by Farran’s 2006 obituaries, with that in The Times particularly notable for its astonishing declaration of his innocence.

Cesarani is the author of a justly praised biography of Adolf Eichmann, and of another less known volume, Justice Delayed, that everyone interested in post-1945 British history should have read. In many ways Justice Delayed is more shocking than his Eichmann biography because with that book we know what to expect. What Justice Delayed revealed was that the 1945-1951 Labour government did its best to keep Jewish Holocaust survivors out of Britain, but had no problem with allowing in Baltic veterans of the SS. While there is nothing as revelatory in Major Farran’s Hat, nevertheless it does lay bare a desperate counter-insurgency strategy that had no prospect whatsoever of success and instead descended into pointless murder. It will come as no surprise to learn that Farran walked away from the crime, wrote a best-selling memoir, stood for parliament as a Conservative candidate in 1950 (he was defeated by the sitting Labour MP, a certain George Wigg), and went on to have a successful political career in Canada. He became Solicitor General in Alberta in the 1970s and later Professor of Political Science at the University of Alberta.

Farran was an authentic war hero, serving in the SAS during the Second World War. He was, as Cesarani shows, very much ‘a child of empire’, someone ‘raised to be an imperial warrior’. It has to be said, however, that his own accounts of his wartime experiences are written very much in the spirit of a ‘people’s war’. In the aftermath of the war, he enlisted in the British campaign against the Zionist resistance in Palestine. Here the British encountered one of the most effective and ruthless guerrilla movements of the post-1945 period. Although Cesarani does not make the comparison himself, it is interesting to compare the methods the British employed against the Zionists with those they used to crush the Palestinian rebellion of the late 1930s. In combating the Zionists the British were restrained compared with the repression they inflicted on the Palestinians, repression in which the Zionists enthusiastically joined. Indeed, the Israeli Army today continues to use the same methods against the Palestinians, although with considerably greater firepower. It is worth making the point here that anyone who compares the collective punishment that Israel recently inflicted on Gaza with the Holocaust, not only shows a shameful ignorance of the horrors of the Holocaust, but also misses the real colonial antecedents of Israeli repression. The Israelis learned how to do repression from the British.

The British were never able to use such draconian methods against the Zionist settlement in Palestine. It had too much international sympathy, particularly in the United States, for the British to make use of the full armoury of colonial repression. There was also considerable support for Zionism within the Labour Party with at least one minister keeping the Jewish Agency fully informed of government policy. This was the context in which the military seized on the panacea of special plainclothes undercover squads, beating the terrorists at their own game. As Cesarani quite correctly points out, this was so much romantic nonsense. He is rightly scathing with regard to those later commentators who have celebrated Farran’s activities as providing a model for successful counterinsurgency.

Any effective counterinsurgency has to be founded on a political strategy that delivers popular support for the military and the police against the insurgents. Some accounts treat a political strategy as if it were merely one ingredient in the development of effective counter-insurgency, but it is better regarded as the recipe. The British had no credible political strategy in Palestine after the War. Whereas the Zionist settlement had originally been sponsored as a way of helping maintain British domination over the Middle East, by the 1940s the British recognised that it was actually damaging the British position throughout the Arab world. If Britain had still been a super-power, it could have ignored Arab opinion in the way that the United States does today, but those days were gone. Instead, the British set out to appease Arab opinion. This provoked armed resistance by the right-wing Zionists and alienated the Zionist mainstream. Unable to either conciliate or effectively repress the Zionists, the British were doomed.

The lack of a viable political strategy showed itself on the ground in the lack of intelligence. Intelligence is the key to operational success in counterinsurgency and the British signally failed to penetrate the Zionist resistance. The scale of the failure is shown by the fact that Farran’s unit did not include a single Hebrew speaker. One suspects that the murder of Rubowitz was at least in part the result of sheer frustration on the part of someone not used to being ineffective. It was an altogether pointless killing, not something carried out as part of a plan, no matter how disreputable. The British did not operate death squads in Palestine as they had done in Ireland in the early 1920s and were to do elsewhere on many other occasions. Instead, Farran just seems to have ‘lost it’. Moreover, as Cesarani points out, there is evidence that the Irgun and the LEHI, the two resistance organisations, had become aware of British undercover operations and would certainly have taken decisive steps to counter them if the Rubowitz affair had not intervened.

Cesarani’s account certainly brings out the ruthless efficiency of the Zionist underground. Arguably, the incident that finally brought home the futility of the British position was the Irgun’s capture and subsequent hanging of two British sergeants on 30 July 1947. This was in reprisal for the British hanging of Irgun prisoners. They also mined the killing ground, injuring the men who cut down the two bodies. This provoked serious anti-Jewish riots in a number of British cities. As far as British public opinion was concerned this episode had considerably more impact than the Farran affair. What Cesarani resolutely avoids in his account is any consideration of the attacks that the Zionists were making on the Palestinians, even while fighting the British.

Farran walked free after a token court-martial presided over by that arch-reactionary, Melford Stevenson. He returned to Britain a hero. The LEHI did make an attempt to assassinate him, but their bomb killed his wholly innocent brother, Rex, by mistake.

Cesarani makes the point that the killing of Alexander Rubowitz is a challenge to the still widely held belief ‘that Britain surrendered its empire ‘gracefully and with dignity’. He goes on to later describe the episode ‘as warning of everything that can go wrong when young warriors directed by desperate and unscrupulous politicians wage war on terror’. The point is well made. Unfortunately such warnings are seldom if ever heeded.