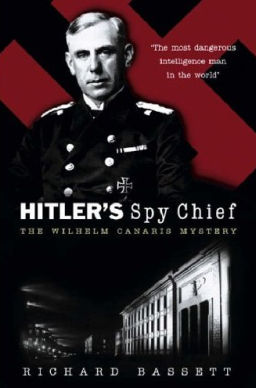

Hitler’s spy chief: the Wilhelm Canaris mystery

Richard Bassett

London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2005, £20

This is a full and very well researched biography of one of the great enigmatic figures of the spy world in the 30s and 40s. The author, former foreign correspondent of The Times in Berlin and Prague, provides much information on the complicated diplomacy of the 1930s and 40s as well as some additional information on the activities of the internal resistance within Germany to Adolf Hitler and the supporters of the movement for a united Europe. The best parts of the book cover the major disaster of British foreign policy decision making in the twentieth century the Munich agreement in 1938 and the very under reported but considerable peace manoeuvres between August 1942 and September 1943.

Despite a background which was quite similar to many centre-rightists within the German officer class, British diplomats, politicians and spies had problems categorising Canaris. They never quite understood his intellectual hinterland. He was described rather sniffily by Military Intelligence, as ‘a kind of Catholic mystic’. Little was produced (by them) to support this assertion, although the author notes that he did apparently enjoy visiting Spanish churches and throughout his career had excellent relations with the Vatican. Canaris is described as shabby, insignificant looking, highly intelligent etc. a man very similar to the anti-hero found in many Graham Greene novels, or a German George Smiley. It is also recorded that he was ‘linked’ to various ‘secret societies’ that were banned in the Third Reich but prominent in Austria, Hungary, Lithuania and Latvia. They presumably formed part of the Catholic lobbying groups, Intermarium, that had been established in the 1930s by the Vatican and whose membership overlapped considerably with that of the Pan European Movement, established by Count Coudenhove-Kalergi in 1923.([1])

The failure to avert war

Like many who had lived through the chaos in Germany between 1918 and 1924, with the apparent re-emergence of many of these circumstances after 1931, Canaris had not been hostile to the formation of a National Socialist-led coalition in 1933.([2]) By 1937, once Hitler had announced his plans for massive military action across Europe, including the conquest of vast tracts of the East, Canaris turned against the Nazi regime, appalled both by the prospect of another continental war and the essentially gangster characteristics of the government. In the difficult circumstances found within a dictatorship, he began plotting its downfall with a diverse array of individuals. By July 1938 Canaris and many in the German High Command, together with civilian politicians left in the country, were preparing an internal coup that would remove Hitler, establish a provisional government and return to democracy. The motives for this were the perceived need to avoid a war with Britain, France and the Soviet Union over Czechoslovakia, all three nations having said they would assist or guarantee the existence of that country. Senior German military figures had correctly predicted (after their experience in 1914-1918) that Germany could not win a war on two fronts and, as Hitler was planning such a venture, he should be forcibly removed.

The coup plans included the arrest of Hitler, followed either by his certification as suffering from mental illness and/or being put on trial, the establishment of a government led by Schacht, von Papen and others, consultation on the future form of democracy in Germany, the disbanding of the SS, and the avoidance of any conflict over Czechoslovakia whilst continuing to seek settlement of other territorial issues by negotiation.([3]) Imagining that such a course of action would have British support, the coup planners sent emissaries to London in August 1938.([4]) These discussions were reported to Neville Chamberlain but his reaction was far from the relief that might have been imagined. This book shows that a reappraisal of Munich and the usual British explanations for Chamberlain’s conduct is very much overdue. For the Prime Minister and many in the British ruling elite the prospect of a stable, centre-right led Germany had little appeal. In particular it was noted that in the period between 1922 and 1933 the German military had co-operated with the Soviet Union. Hitler had been much more reliable than this. He had stopped the military co-operation, he had crushed the alleged Communist threat in Germany and was regarded by many influential figures in Britain as the best bastion civilisation could have against Soviet expansion. The author puts a very forceful case that Chamberlain’s sudden flight to Germany to placate Hitler was specifically undertaken so that a deal could be done with him about Czechoslovakia before the coup could be carried out. ([5] )

The failure to stop war

The second intriguing section of the book covers the attempts by three groupings to reach a compromise peace between September 1942 and November 1943. These could broadly be described as the Hitler-Stalin proposal, the Canaris-German resistance-Vatican proposal and the American proposal.

The first approaches were made, in September 1942, by the Soviet Union to Germany. With German forces at the Caucasus, just outside Cairo and fighting their way through Stalingrad, and the US seemingly bogged down in the Solomon Islands, the Soviet leadership considered that British and US efforts would take many years to come to fruition. They thought the Soviet Union would be bled dry in the interim. The Soviets offered a peace and a retreat to mutually acceptable borders. By the end of the month neutral ambassadors in Berlin and Moscow were reporting credible moves between Germany and the Soviet Union to reach terms. The German reply to the Soviet approach mentioned by Hitler to the Japanese ambassador was to propose a new border which would include the Baltic States, Belarus and the Ukraine all being retained by Germany or within the German sphere of influence. By November 1942 delegates from both Germany and the Soviet Union had met in Stockholm to discuss this. At this point, though, military reversals began impacting on the German negotiating position. The British were victorious at El Alamein on 4 November and the German VI Army was encircled at Stalingrad by 27 November. The Hitler-Stalin proposal thus moved more slowly than expected. Neither party had quite the motive that they might have had a few months earlier to move it to a speedy conclusion.

Simultaneously with this and possibly partly in reaction to it the Vatican had contacted Franz von Papen in ‘the late summer of 1942’ asking if he could broker a peace between Britain, Germany and the US (but, note, not the Soviet Union). Pope Pius XII himself arranged meetings, the objectives of which would have been the removal of Hitler, the disbanding of the SS, a centre-right government in Germany, the Soviet Union being swept out of eastern Europe and the launch of a ‘European Economic Union ‘, in which the Vatican would have some influence. Throughout October and November 1942 talks between various emissaries were held on how best to move this forward. News of this reached Stalin who ordered the murder of von Papen, delegating this to a team of Bulgarian assassins, who blew themselves up in the process, leaving von Papen unharmed.

In the meantime British Military Intelligence had learnt of the Hitler-Stalin proposal. A study presented to the Foreign Office ‘in late 1942’ recommended that the war in Europe could be ended if the German General Staff were given a clear incentive to launch a coup. Essentially the authors of the document were arguing that the Foreign Office should back the Canaris-German resistance-Vatican proposal. This report had to cross the desk of Kim Philby a Soviet agent before it could be officially circulated to Ministers. Philby duly rejected the document, thus blocking any formal discussion of a peace deal that would be to the disadvantage of the Soviet Union.([6])

This now put Britain and the US in the position where, in order to dissuade the Soviets from continuing discussions with the Nazis, they had to reassure them of their intentions. This they did at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 with the announcement to the great dismay of Canaris, the Vatican and the German resistance of the ‘unconditional’ surrender policy. Despite or perhaps because of this there was now a US initiative to see if a peace deal could be struck with Germany.

The American proposal was made in February 1943, by Allen Dulles, in Switzerland to Prince Max von Hohenlove,([7]) (a representative sent by Schellenberg (a Nazi), who also had good connections with the Canaris grouping. Dulles told Hohenlove that the US would broker a compromise peace in Europe if Hitler were removed and if ‘Europe could be a large and extensive market for US commercial interests’ meaning, presumably, that there would be no European Economic Union. Dulles also said that the US were prepared to agree an extensive rearrangement of borders in Eastern Europe, similar to those sought by Hitler and Ribbentrop, with Germany also keeping Austria and ‘the Czech areas’; ([8]) and Central Europe would be tidied up with a ‘cordon sanitaire’ and a Danube Confederation, something advocated by the Vatican, the Habsburgs and Intermarium since the 1920s.([9]) Seeking, perhaps, to pursue this opening given the silence from the British the German resistance made two attempts to kill Hitler (13 and 21 March 1943).

Meanwhile the Hitler-Stalin proposal flickered back into life. In June 1943 serious talks were held in Stockholm and there was possibly a meeting at Kirovograd, within the German lines, between Ribbentrop and Molotov to see if the war in the east could be ended to the satisfaction of both parties. ([10]) The subsequent failure of the German offensive at Kursk (July 1943) and the Soviet demands increasing after this for a return to the 1939 frontiers, led to the discussions fizzling out in September 1943, never to be renewed.

The last throw of the dice came in October and November 1943 with direct talks in Turkey between von Papen and the Middle East representative of Readers’ Digest, Theodore A. Morde, in which the US position was again stressed: Hitler should be removed prior to a separate peace being arranged.

The German resistance faced great difficulties in carrying out its plans due to the highly oppressive and intrusive nature of life in the Third Reich. It may also not have been clear to some German anti-Nazi figures what they would gain by going along with the American proposal. After all, the intrusion of the US into Europe in 1919 under Woodrow Wilson had been seen by many as the cause of the difficulties that led to such chronic instability on the continent.([7]) Once the Soviet Union had a significant military advantage, Stalin and his colleagues lost interest in dealing with the Hitler regime. And for many in Britain and the US the critical issue was that German power in Europe should be destroyed or very severely curtailed, not given the chance to re-emerge at the head of a united Europe.

Finis Canaris

This was the grim tragedy that befell Canaris. His views a strong Europe, heavily allied to the Vatican were incompatible with the US option, a Europe in which America had a commanding presence. Having finally fallen out with key supporters in the Nazi hierarchy (who had noted his lacklustre performance as an Intelligence Chief for some time) he was removed from his position as Head of the Abwehr in April 1944, arrested in July 1944 after the final failed attempt by the German resistance to murder Hitler and killed in prison in March 1945.

This book demonstrates that the issues that split Europe apart 60 years ago have a direct connection to current debates about the status of the US and its role in the continent. The British, and in particular the faction that actively prefers the US to Europe, emerge from it with little credit. The point about seeing Chamberlain and Munich in a different and somewhat more scandalous light is well made by the author. It is also clearly the case that the pivotal role of Philby, in 1942-1943, in hiding how anxious the German resistance were to end the war, is surely a far greater crime than the usual allegations made against him. A coup against Hitler at that point would have had the immediate result of the rounding-up of the SS, the opening of the camps and the end of the Holocaust. Millions would have lived. The usual charge against Philby that he ‘probably’ caused the deaths of various British and émigré agents in the 1945-1950 period is minor by comparison. Some publicity for this would be welcome.

Notes

[1] The Pan European Union was founded in 1923 by the former Austro-Hungarian aristocrat, Count Coudenhove-Kalergi. Their website shows that it was clearly the driving force behind the creation of the European Union.

[2] Canaris did not hold a senior position in 1933: he was commander of a training ship.

[3] Hjalmar Schacht had been a founder member of the German Democratic Party in 1919. He was sacked as Minister of Economics in 1937 after opposing the scale of German rearmament and later sacked as President of the Reichsbank in January 1939 after similar protests and proposing a Jewish refugee plan. In the summer of 1938 he had told Montagu Norman at a meeting of the Bank of International Settlements in Geneva of the plans to oust Hitler. Norman told Neville Chamberlain, who replied, ‘Who’s Schacht? I have to deal with Hitler.’ Franz von Papen, who had briefly been Chancellor prior to Hitler (June-November 1932), was a significant figure in the Catholic Centre Party and was well connected to both the Vatican and the German army.

[4] The main German emissary, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin, a significant land owner in Prussia with pronounced Christian leanings, met with Lord Lloyd, a former High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sir Robert Vansittart, a career diplomat who actually had little influence with Chamberlain, and Winston Churchill. Churchill told Lord Halifax of the intentions of the German conspirators. Halifax relayed this to Chamberlain. Other anti-Hitler figures who came to the UK in 1938-1939 liaised with Klop Ustinov, father of the actor Peter, in London. Klop Ustinov was a Baltic German previously in the service of the Tsar of Russia, who worked closely with British military intelligence.

[5] Chamberlain flew to see Hitler the day before Hitler was due to order military action against Czechoslovakia. He had never flown before, took no interpreter and did not speak German.

[6] See The Daily Telegraph obituary of Professor Sir Stuart Hampshire, 15 June 2004. Hampshire was one of the authors of this report. Philby dismissed it as ‘mere speculation’.

[7] Prince Max von Hohenlove was married to the sister of Prince Philip. His son married a Fait Heiress. Hohenlove seems to have moved in the same circles as many in the German resistance in 1938-1939 without falling foul of the Nazis, or perhaps having a continuing use to them via his personal connection to many in European royalty.

[8] He also suggested that the SS should ‘act more skillfully’ on Jewish matters to avoid ‘causing a big stir’.

[9] Dulles, later head of the CIA, had been approached by the Vatican to intercede on behalf of the German resistance after the policy of ‘unconditional surrender’ was adopted. Hence perhaps the mixture of items that would be favourable to the Vatican whilst others that ran counter to historic US intention (the European Economic Union) being discouraged. By 1943 the US had taken over funding the Pan European Movement from Britain.

[10] The negotiations in Stockholm definitely took place. The meeting in Kirovograd is less certain but is referred to in Liddell Hart’s The Second World War, pp.510-511.

[11] One might add that as well as causing territorial disputes with a version of National Self Determination that excluded Germans, Hungarians and many others. Wilson’s lofty Liberalism was at its hardest in the economic sphere with the destabilising demands for reparations and the desire to open up Europe to US commercial interests surely an early version of the US desire not to have a serious economic competitor in Europe.