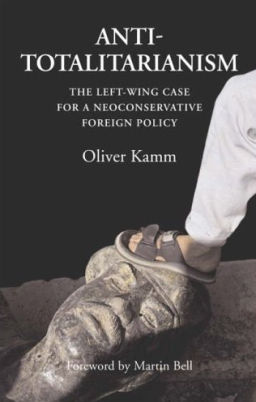

Oliver Kamm

London: The Social Affairs Unit, 2005, h/b, £13.99

Kamms’ Anti-totalitarianism was published in the same week and possibly on the same day as the Henry Jackson Society announced itself to the world. So this is a kind of manifesto for that group. (1 ) It’s a nice try, in a way, this pretence by Times columnist Kamm to be a left-winger. (For Kamm ‘left-winger’ means being a member of the Labour Party). It gives him a pitch – ‘left’ support for the Iraq War/’war on terror’ – that the media are supposed to find interesting. You can probably guess his major arguments but you might be surprised by the boldness of his position. Here’s the essential move he wants us to make:

‘Iraq was not the biggest blunder since Suez; it was the most far-sighted and noble act of British foreign policy since the founding of Nato (2) ………… after 9/11, Bush’s instinctive conservatism gave way to promoting global democracy as our defence against theocratic barbarism – a strategy that accords with traditional liberal-democratic internationalism.’ (p. 19)

Yes, you read that correctly: invading Iraq is ‘the most far-sighted and noble act of British foreign policy since the founding of Nato’.

Kamm takes us through a cartoon-simple version of the Cold War in which America and Britain resisted the Soviet menace and tried to spread freedom. (3) Along the way he revisits old arguments. Take the opposition in the early 1980s to the deployment of Cruise and Pershing missiles in Europe. For Kamm, these reflected

‘….a curious belief – reinforced by loose talk from a new President, Ronald Reagan – that a new generation of intermediate missiles was being deployed in order to fight a “limited” nuclear war in Europe. The notion was preposterous. The rationale for Nato’s deployment was the opposite.’

At best, Kamm hasn’t done his homework. There was a good deal of nuclear war-fighting talk among the Pentagon and its satellite think-tanks and university departments. It was all the rage among the strategic theorists in the late 1970s. The issue was the credibility of the US nuclear threat. There was a long-standing obvious problem with Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), the theory upon which nuclear deterrence then rested. In the early Cold War years NATO believed – or pretended to believe – that the Soviet invasion of Western Europe was being prevented by the threat of a nuclear attack by NATO (i.e. the USA). But once the Soviets had their own stock of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), such a threat looked implausible for it entailed – that’s right, mutual destruction. So the rationale for nukes shifted from being a means of deterring the Soviet tank invasion of Western Europe to that of a means of deterring either side from using nukes. At which point the nukes became useless as weapons (and, equally useless at deterring that hypothesised Soviet tank advance, which, curiously, never took place). Strategic theorists began trying to find a way out of this, a way to make nukes work as weapons. The answer was variations on: use smaller nukes – useable, war-fighting nukes – which won’t lead to a full exchange of ICBMs This debate got intense in the late 1970s when the Soviets deployed intermediate range missiles (missiles which would not reach the USA) when NATO (i.e. the US, chiefly) had none of similar range. Here’s Kamm’s version of this.

‘If the Soviets threatened to use missiles in the European “theatre”, and Nato had no weapons of comparable range but only the US strategic arsenal with which to retaliate, then they [the Soviets] might calculate that the US would be deterred from retaliating.’

Why would they be deterred from retaliating? Because – and this is the bit Kamm doesn’t want to state – retaliation meant that the US would decide to commit national suicide by having an ICBM exchange with the Soviet Union, ‘in defence of’ Europe. And how likely was that? On the other hand, intermediate range missiles, based in Europe, meant the threat to use nukes might mean only fighting to the last European. (Echoes of Vietnam and destroying a village to save it.) Thus, went the argument, deploying Cruise and Pershing as intermediate-range missiles in Europe, made the threat of American nuclear retaliation more ‘credible’ – i.e. they might conceivably use them – and so tied America more closely to Europe.

Without getting the books from the period out of the attic, I remember the counter-argument which pointed out that the range of missiles available to NATO, without Cruise and Pershing deployment, included not merely the ICBMs based in the United States, but also US (and the UK) submarine-based missiles. (There was also the obvious, rather telling point, that this scenario presupposed that under attack from US missiles based in Europe the Soviets would not retaliate against the US mainland.) In other words, the rationale for the introduction of Cruise and Pershing made no sense even in the terms of NATO’s strategic theorists. Kamm’s argument falls on its face – just as it did in 1980.

There is almost nothing Kamm won’t embrace in his enthusiastic reaffirmation of Cold War idiocies.

‘Reagan, ever the butt of jokes about being simple and ill-informed, was a complex man with intellectual depths and subtle nuances to his politics’. (p. 59)

Kamm retells Denis Healey’s account of Reagan mistaking Healey for the British Ambassador and dismisses it.

‘It seems likely…..that Reagan was acting a part here, playing up to his image as (in the phrase of Clark Clifford) an amiable dunce.’ (pp. 59/60) (4)

And so on and so on.

The point of Kamm’s crude, flip-flop revisions and attempted sleights-of-hand is to try and link post-war anti-communism with the current anti-Muslim strategies in what the Bush regime has now designated as ‘the long war’ between ‘freedom’ and ‘totalitarianism’. Once it was communist totalitarianism and now it is Muslim totalitarianism: same struggle, different enemies. This is clearly going to be the new line: the struggle against totalitarianism that has already lasted 60 years. We can’t be very far from some American think-tanker talking about the Second Hundred Years War.

Notes

1 <www.henryjacksonsociety.org/> This is the latest in a long line of British outfits cheer-leading for American imperialism and military power. There has been no evidence yet of American money/control involved with this but we wouldn’t be greatly surprised if there was, would we, given the timing of the organisation’s appearance and the particular ‘pitch’ it is offering. If this was the 1950s or 60s we might assume it was an example of classic CIA funding of a putative left group. But these days, who knows?

2 Notice that he, like almost everyone else these days, writes of Nato and not of NATO. After the Cold War ended and NATO began to redefine itself and to extend its life and its field of operations, so it renamed itself Nato, in the hope, I presume, that we would forget what the acronym – and thus the original purpose – stood for.

3 The evidence since the collapse of the Soviet bloc suggests that the most important aspect of the Cold War was the role of the Soviet bloc in keeping American imperialism under some kind of control. Without those restraints we have the world that we see today.

4 Amiable dunce is about right but the failing memory was an early sign of the Alzheimer’s which eventually killed him.