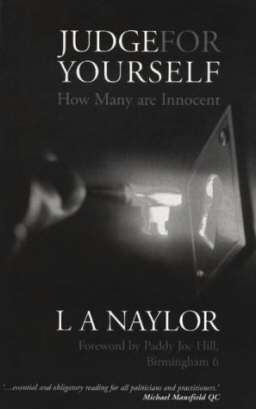

L. A. Naylor

London: Roots Books, 2004, £12.99, p/b

This book sets out to show how miscarriages of justice come about, and how difficult and protracted is the process of getting a wrongful conviction overturned.

An estimated 3,000 wrongfully convicted people a year go to prison, according to a Home Office bulletin, and between 1969 and 1999 more than 1,000 people were killed while in police custody; yet not one officer has been successfully prosecuted for a death.

The role of police corruption defined as ‘the exploitation or misuse of authority, typically characterised by bribery, violence and brutality, the fabrication, destruction and planting of evidence’ in creating miscarriages of justice is examined. Shockingly, those responsible for causing or perpetrating a miscarriage of justice are not held accountable: ‘one of our deepest concerns should lie with the fact that the criminal justice system is ineffective when it comes to bringing corrupt police officers to justice.’

The book describes how one of the main causes of miscarriages of justice is non-disclosure to the defence of relevant evidence that could undermine the prosecution case. Maybe this isn’t surprising, as it is the police who decide what is disclosed to the crown prosecutors, who also rely on the police for their materials and information. The Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 is strongly criticised for exacerbating this problem, as it allows the police to withhold material from the defence. Sometimes evidence that could aid a defendant is withheld using the doctrine of ‘public interest immunity’.

Forensic evidence may be flawed. The author describes how DNA evidence, although an important tool, can have a large subjective component, or, if not handled carefully, can become contaminated; and fingerprint evidence, previously regarded as foolproof, can be fallible. Statistics, such as the probability of a false DNA match, can be presented to the jury in a misleading way.

The Criminal Cases Review Commission, the body responsible for investigating suspected miscarriages of justice, comes in for serious criticism, and, the author says, ‘still failed to deliver any semblance of redress for the majority of people who insisted they had been wrongfully convicted.’ Although the CCRC can seek information relating to a case, and carry out it’s own investigations, research quoted in the book indicates that it often fails to do so, and it is still dependent on the police to carry out re-investigations of its cases. Proportionately few cases get referred back to the Court of Appeal, the route by which a wrongful conviction can be overturned: ‘In 2001 the Commission reviewed 885 cases and made final negative decisions on 853 of them… what disturbs me most is the fact that the CCRC currently expends over £6 million a year to refer just 30-odd cases.’ Many people feel that the statutory framework, the Appeal Act, should be changed, so as to allow the CCRC to refer all cases where there is a real possibility that a miscarriage of justice has occurred, rather than the current situation, where there is a real possibility that the Court of Appeal would not uphold the conviction.

The book illustrates how wrongfully convicted prisoners who are ‘in denial of murder’ can end up serving many years over their tariff and more than if they had been guilty. Stephen Downing, who served 28 years before being released (and then only after investigations lasting eight years by the journalist Don Hale) could have been released on parole 10 years earlier if he had admitted guilt.

A large part of the book is devoted to the often shocking testimony of prisoners, both those still inside and protesting their innocence, and those who have been released, including Robert Brown, who was convicted of murder in 1977 after being fitted up by corrupt police officers, and released in 2002 after serving 25 years, all the time protesting his innocence. He refused earlier parole because it was offered on condition he admitted to the crime. He describes how he endured the system, and, remarkably, is able to say: ‘I’m not bitter either. I’m capable of taking a look around the world and living in the knowledge that there are people much worse off than me.’

Release from prison is often only the start of a new set of problems. There is no organised system of professional help for those released on appeal, despite the often serious social and psychiatric problems experienced by those who have been released after wrongful imprisonment. Psychiatric assessments of those wrongfully convicted and sent to prison show that victims of miscarriages of justice have enduring personality change and impaired ability to function in normal social and interpersonal relationships. The continuing psychiatric problems experienced by ex-prisoners is illustrated by Paddy Hill, of the Birmingham Six, who, ten years after his release, reports ‘chronic symptoms of tension, rage, anxiety, depressed mood and sleep impairment’.

The author ends with a call for action and change to prevent miscarriages of justice, urging people to get involved and campaign, and is encouraged by the powers of the new Independent Police Complaints Commission, which can investigate incidents of alleged police misconduct separately from the police:

‘The issues we need to debate include the ongoing dilemma over disclosure rules and the fact that forensic evidence may be seriously flawed. We desperately need to focus on getting innocent people out of prison and we also need to question why a greater proportion of corrupt police officers are not brought to justice…….in the interests of justice it is vital that an independent investigation takes place to investigate allegations of police corruption…once evidence of corruption comes to light, the criminal justice system should immediately arrange for the investigation of the police officers involved and issue an unreserved apology to the wrongfully convicted, with a public statement acknowledging the innocence of the appellant. It’s time judges in Britain moved beyond addressing the technical ‘safety’ of a conviction and had the guts to apologise to its devastated victims of injustice.’

This book should be read by anyone with an interest in the criminal justice system, but its message is relevant to us all: as Paddy Hill says in the Foreword: ‘One of the things that the public find hard to understand is just how easy it is to be put in prison for a crime you did not commit.’