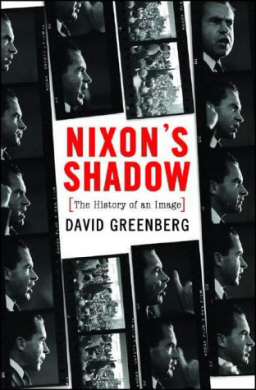

David Greenberg London: W.W. Norton and Co, 2004, p/back, £9.99

A few years ago, during one of America’s periodic re-evaluations of Richard Nixon, cartoonist Gary Trudeau showed Mike Doonesbury’s young son watching the ex-president on television. After a panel’s worth of contemplation, the boy asks, ‘He’s lying now, isn’t he?’ The parents beam with pride. ‘A new generation recoils!’

In this study of Nixon’s image-making, and America’s perception of it, David Greenberg recoils not at all. This could be seen as academic neutrality, but as we discovered during Nixon’s presidency, reporting the official version uncritically endows it with a veneer of truth. The weakness of this approach becomes evident quickly. Greenberg reminds us that Nixon was chosen to run for Congress in 1946 because he was considered attractive to the voters. His Nixon is an honest populist, campaigning against Eastern elites soft on communism.

But the more important part of that equation was the idea that Nixon was ‘chosen’. To Greenberg, the businessmen who selected Nixon as their candidate were a collection of mom and pop storekeepers, but they were bigger fish; Greenberg himself quotes one of the Crocker Bank family. And how accurate can analysis of Nixon’s image be if it ignores the influence of Murray Chotiner, the spiritual godfather of negative campaigning? It was Chotiner who ‘sold’ Nixon to the voters as a war veteran with an attractive young family. How can we evaluate that image if Greenberg ignores his wartime position in the Office of Procurement, and his early dealings with his shady friend, Bebe Rebozo, who is mentioned only once?

Nixon based his career on the politics of resentment. Greenberg traces each campaign, but plainly doesn’t accept Nixon’s tactics as being negative, though the same techniques become suspect when they are adopted by George Wallace in 1968. Why does Greenberg not sauce the gander as well as the goose?

Rather than the shortcomings of academic balance, the blame for Greenberg’s approach is more reasonably attributed to America’s current political template, as forecast by Nixon’s campaign manager and attorney general, John Mitchell, who said, on his way to prison, ‘This country is going so far to the right you won’t recognise it.’ By adopting the context which rules America’s major media, Greenberg can characterise the victims of Nixon’s California campaigns, Jerry Voorhis and Helen Gahagan Douglas, as ‘liberals’, far outside the American mainstream. Of course, at the time, they were not; and it was Chotiner’s reliance on the meekness of a media frightened by red scares which predicated Nixon’s slinging of mud.

The nadir of this approach is Greenberg’s portrayal of the success of the Checkers speech, the very litmus of Nixonian insincerity. He explains its appeal to believers, but stretches credulity by suggesting the 1956 election result marked Nixon’s triumph over the ‘egghead’ Adlai Stevenson. This ignores the overwhelming appeal of Dwight Eisenhower as a candidate, regardless of running mate.

Greenberg has also adopted the locutions of mainstream punditry, particularly the unsubstantiated ‘most’. If, in 1971, ‘most’ Americans really embraced Nixon, why would his reelection campaign have avoided referring to him by name? If they had, they would have avoided the deliciously telling acronym ‘CREEP’ (Committee To ReElect The President).

To accept that Nixon’s negative reputation was solely an image problem, one must also dismiss much history as conspiracy paranoia. Greenberg sees Nixon’s worst excesses as justifiable reactions to equally ruthless enemies, like the effete liberals of the 40s and 50s or the student radicals of the 60s. To suggest equally-matched opponents, he quotes without scepticism a figure of ‘30,000 bomb threats’ received during the Sixties, trying to recast the vast anti-war movement into a prototype Al-Qaeda. Respected reporters like Seymour Hersh get lumped in with off-the-wall radicals; others, like Jim Hougan, are marginalised completely. There is no mention of Nixon and Kissinger’s sabotaging of the 1968 Paris peace talks (an early ‘October Surprise’), no discussion of Nixon’s links with Howard Hughes, and the links to that vast intelligence underworld.

Nixon’s defining moments, the Watergate scandal, his impeachment, and resignation, exist in a similarly conspiracy-free light. Greenberg repeatedly quotes with approval those reporters who admit to having been fooled by Tricky Dicky. Their sympathy, engendered by his ‘you won’t have Nixon to kick around’ speech after losing the 1962 California gubernatorial elections, led them to accept Nixon at face value in 1968. The press gave Nixon a free ride in 1972, against the ‘unelectable’ McGovern. Watergate remained a non-issue until the lies became too blatant to dismiss. Greenberg, who worked on Bob Woodward’s Clinton book, The Agenda, never even wonders about the identity or motivation of Deep Throat.

Nixon held the press off for a while with attack, the same sort of howling about the ‘liberal media’ which dominates the media today. It seems to have worked so well that Greenberg appears desperate to avoid being labelled a ‘nattering nabob of negativism’ by Spiro Agnew.

After Nixon quit the White House, he was reborn as an elder statesman, hailed for his real politik with the Soviet Union and China. Here Greenberg is more comfortable, tracing deftly Nixon’s academic reevaluation as a ‘liberal’, the last Republican President not committed to destroying the New Deal. One can argue that the movement within the Republican party in the second half of the last century has been steadily toward returning to the glory days of Warren Harding. If Bush Senior were Calvin Coolidge in all but taciturn name, that makes ‘Shrub’ Herbert Hoover.

We can speculate about the motivations behind Nixon’s ‘liberalism’, but Greenberg dismisses the ‘psycho-biographers’ who were attracted to Nixon as an early case-study. His analysis of those dismissed is cogent, but although he quotes Gary Wills a number of times, he omits Wills’ Nixon Agonistes, one of the first, and still the best of the genre. More a literary exegesis than psycho-biography, it analysed Nixon’s images better thirty years ago than Greenberg can now.

Greenberg’s conclusion is that Nixon’s legacy means Americans now ‘routinely believe all Presidents manipulate images’. But the reality goes far deeper. Thanks to Nixon, ‘character’ has become the bullfighter’s cape of political analysis, used by spin doctors and media alike to distract their audience. The next time a group of Republican businessmen in California sought a viable candidate, they chose someone you would buy a used car from, the B list actor Ronald Reagan. The outpouring of uncritical praise following his recent death merely confirmed the triumph of his image over reality.

In the last Presidential election, Al Gore was the Nixonian ‘liar’, while George W. Bush, sporting the American flag lapel pin introduced by Nixon as self-conscious refuge in patriotism, proved himself presidential simply by not stumbling, à la Gerald Ford. Not surprisingly, Bush’s Svengali, Karl Rove, was a young Nixon campaign worker. Perhaps because Bush’s lip-licking smirk is the most revealing ‘tell’, identifying mendacity, since Nixon’s phoney smile, and his chimp-like visage the greatest boon to cartoonists since Nixon’s jowls and ski-jump nose, the ability of Rove’s candidate to generate visceral protest and resentful support is strikingly Nixonian.

Strangely, in a study of image, Greenberg gives short-shrift to Nixon’s rich catalogue of portrayals in fiction and film. He is particularly dismissive of Oliver Stone’s movie Nixon, which, for all its horror-film iconography, is both more sympathetic to Nixon and closer to Greenberg’s own thesis than he might like to admit. Greenberg quotes Nixon saying that those who lie or cover up tend to reveal themselves by overreacting. That resembles the Jungian theory of the Shadow, whereby we hate in others what we fear in ourselves. In a key moment of Stone’s Nixon, Anthony Hopkins, as Nixon, talks to a portrait of John Kennedy. ‘When they look at you, they see what they want to be; when they look at me they see what they are.’ The essence of Nixon’s image is that the shadow is not his, but America’s.