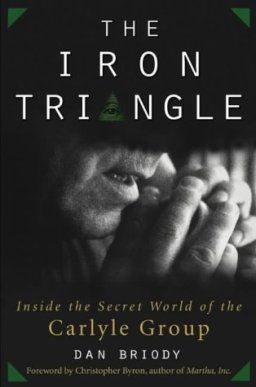

Dan Briody

Hoboken (USA): John Wiley and Sons, 2003, £17.50 (hb)

According to the Carlyle Group, once you ‘peel away the layers of factual errors and self-righteousness of The Iron Triangle, ‘… all you’re left with is baseless innuendo… [and]… this book should be exposed for what it is: a compilation of recycled conspiracy theories masquerading as investigative journalism.’ Given such a view it is hardly surprising that the Carlyle Group forbade its employees from talking to Briody. However, despite such obstacles, with insight, erudition and a deft pace Briody has succeeded in producing a remarkable account of the meteoric rise of the Carlyle Group from its inception in 1987 to its emergence today as one of the largest and most powerful private equity firms in existence.

While rival private equity firms are traditionally based in Chicago or New York, the corporate offices of the Carlyle Group, unofficially valued at $3.5 billion, is on Washington DC’s prestigious Pennsylvania Avenue, mid-way between the White House and the Capitol building stark testimony indeed to the political power wielded by a firm at the apex of the military-industrial complex.

Until recently few people will have heard of the Carlyle Group, a ‘private equity’ firm that specialises in raising capital from individuals, institutional investors and pension funds and investing it on their behalf, not in stocks, but in purchasing whole companies with the intention of turning them around and selling them for profit. And a very large profit at that: the Carlyle Group currently manages funds worth approximately $14 billion with an average investor return of 36 percent. But what differentiates the Carlyle Group from its competitors is not so much its early concentration and specialisation in heavily regulated industries such as defence contracting (in Britain it recently purchased a major stake in Qinetiq, formerly the Ministry of Defence Defence Evaluation and Research Agency) but the porous borders between politics and business of which the Carlyle Group is the supreme embodiment.

And herein lies the crux of the matter when discussing the ‘ex-President’s club’. As Briody notes, the Carlyle Group has ‘more political connections than the White House switchboard.’ It’s luminaries include former President George Bush (Carlyle’s senior adviser on Asia), Frank Carlucci (former CIA deputy director and Defense Secretary in the Reagan era and now Carlyle emeritus Chairman), James Baker III (Bush’s Secretary of State and senior Carlyle counsellor) and John Major, (the former British Prime Minister and chairman of Carlyle Europe). While its advisory boards are packed with a host of corporate executives from firms like Boeing, BMW and Toshiba, the Carlyle Group can also rely on the business acumen and contacts of figures such as former Philippines president Fidel Ramos and former Thai premier Anand Panyarachun; former Bundesbank president Karl Otto Pohl, and Arthur Levitt, former chairman of the Security and Exchange Commission, the US stock market regulator. Such a roster ensures that multi-million dollar deals are done with ‘a drink and a wink’ by old friends and political cronies. In many cases these figures have passed through the revolving door between political office and boardroom (and in the case of Colin Powell back again) giving the Carlyle Group the inside track on policies and budgets which these figures had until recently presided over, thus raising the spectre of figures like Carlucci reaping massive profits from his knowledge of policies he himself implemented whilst a public figure.

As Briody shows, the ability to mobilise such prestigious ‘ambassadors’ as George Bush Snr. in the corporate cause has enabled the Carlyle Group to make massive inroads into Saudi Arabia which might otherwise be far harder to penetrate. Indeed, following the 1991 Gulf War figures like Bush Snr. and Baker are revered as saviours by the ruling elite’s of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. The resulting nexus of political and personal relationships has enabled the Carlyle Group to emerge as the ‘gatekeeper’ for foreign investment in the Kingdom and vice versa. Another example would be South East Asia where the company has its eye on the real prize: China.

One particularly fascinating point raised by Briody in his examination of the relationship between the House of Saud and the Carlyle Group is its role as a proxy for American foreign policy, through its subsidiary the Vinnell Corporation, which trained the Saudi National Guard, the foremost tool of internal repression in the Kingdom. It was developments such as these and the massive American presence they entailed which have become a potent recruiting standard for Islamic extremists. Having contributed to this ferment, nothing underlined the intersection of American foreign policy with international terrorism and radical Islam than the extraordinary twist of fate which saw the Carlyle board (including, according to some accounts, Bush Snr. himself) watching the events of 11 September 2001 in the presence of Saudi investors like Shafiq Bin Laden, estranged brother of Osama.

In the wake of such events and in line with wider neo-Conservative foreign policy objectives, the Carlyle Group has sought to divest itself of its dependency on the querulous House of Saud in favour of the new ‘opportunities’ emerging from a now pliable Iraq (thanks, no doubt, to the generous economic ‘reforms’ introduced under Order 39 which allows for the wholesale auction of Iraqi assets to multinational corporations). If ever there was a candidate for a firm flagrantly profiting from the ‘war on terror’ it has helped to fuel this has to be it.

The immense political influence of the Carlyle Group and the inherent conflict of interest therein is underlined by G. W. Bush’s woefully inept forays into foreign policy which have increasingly put America at odds with Saudi Arabia and South East Asia where Bush jeopardised Carlyle’s $2 billion investment in South Korea by placing North Korea on his ‘axis of evil’. As Briody highlights, such reckless endangerment of Carlyle Group assets and lets not forget father’s own fortune and his inheritance induced George Bush Snr. to take the unprecedented step of telephoning Crown Prince Abdullah, (according to some reports, in the presence of his son), in order to assure him that not only was juniors’ ‘heart was in the right place’ but that he would ‘do the right thing’. Improper influence? Conflict of interest? Perish the thought!

As an introduction to the Carlyle Group and ‘access capitalism’, Briody’s book is warmly recommended. However, for those Lobster readers for whom time is of the essence, there is a vast amount of material on the internet dealing with the Carlyle Group particularly the excellent series of articles in The Nation and an especially illuminating documentary originally broadcast by VPRO Netherlands TV and featuring extensive interviews with both Briody and Carlyle Group co-founder Stephen Norris. (6)