Responsibilities, old boy

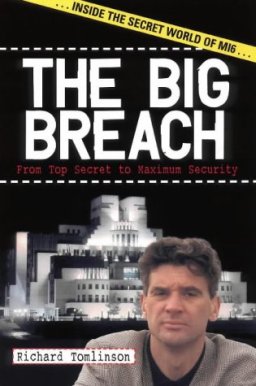

The Big Breach

Richard Tomlinson

Cutting Edge, Edinburgh, 2000, £9.99

I found it hard to ‘see’ this because so much of its contents have been published in the media. There have been some changes – names altered – since the newspaper versions; and I am told that the original hardback version is slightly different though I have not been told in which ways. Notwithstanding all that, here are the bits and pieces I found of most interest on reading the book version.

In one section pp.48-49 (which also appeared in the Sunday Times on 4 February) Tomlinson describes how his intake of new SIS recruits were briefed by the then SIS chief McColl. One of the new recruits put the obvious question:

‘ “Sir, why do we have an intelligence service at all? There are countries more important on the world stage, with much more powerful economies, who have only small or nonexistent external intelligence gathering operations. Japan or Germany, for example. Could the money Britain spends on MI6 not be spent better elsewhere, on health care or education?’

A flicker of a smile crossed McColl’s lips.

“Ah, young man, you overlook the fact that we are still on the United Nations security council, unlike Germany and Japan. Britain has international responsibilities much greater than its economic wealth might suggest.” ‘

Ah yes, responsibilities, the white man’s burden, the Great Game and all that. Which century are we in?

Even more striking is the section of p.169 describing how

‘….under pressure from the Treasury, MI6 had admitted a team of specially vetted management consultants to look at productivity. They treated CX [secret intelligence] and agents as widgets and introduced an “internal market” system. P4 was given targets for how much CX his section had to produce per month and how many agents it had to cultivate and recruit per quarter…’

That this supposed bunch of super bright people allowed into SIS the management guff which has afflicted much of the rest of the public sector, is perhaps the most staggering thing I have ever read about the British intelligence and security services – far more interesting and surprising to me than the details of operations given here. The expression mind-boggling idiocy comes to mind.

And this nonsense had the same consequences in SIS as it has elsewhere in the public sector: faced with career-breaking targets and quotas, people fake them – just as they did in Stalinist Soviet Union where everybody met their quotas but nothing got done or made; and, as every school teacher in Britain knows, just as they have been doing in education since this nonsense was introduced there.

Tomlinson notes after this section that his immediate superior was passing as genuine CX what Tomlinson knew to be propaganda from one faction in the Balkans war:

‘[He] was blatantly ignoring my judgements as the officer on the ground so as to satisfy targets imposed by faceless management consultants.’ (p. 270)

Why SIS management went to the lengths they did to get rid of him is entirely unclear. On Tomlinson’s account it is some kind of petty conspiracy, a personality clash. If I had to guess I would look here, at his resistance to playing the new game of meeting spurious targets.

The introduction of this management bollocks at the behest of the Treasury also raises questions about who has the real power in Whitehall. Tomlinson quotes one of his superiors as saying that no-one can tell the Chief of SIS what to do. Indeed, Tomlinson makes much of this as being at the root of his conflict with them (pp.199/200). But the imposition of this management theory nonsense shows that SIS had to do what the Treasury wanted – even when it was manifestly stupid.

Of the new SIS building he notes (p.175):

‘It was supposedly built to an official budget of £85 million, but everybody in the office knew that in reality it had cost nearly three times as much. We were warned in the weekly newsletter that discussion of the cost over-run would be considered a serious breach of the OSA….’

And they got away with it, of course. (It is a pity Tomlinson didn’t leak some copies of those internal bulletins……)

The fact that so much of the book’s content has already been trailed in the media should not obscure the fact that this is the first detailed account of SIS recruitment, training and operations in the modern world. (Tomlinson conveys rather well what terrific fun it can be being a spook.). And it is indeed a big, big breach of the Official Secrets Act.(1)

Notes

- But not the biggest, currently. That title must go to the on-going leaking of material about the British Army’s FRU in Northern Ireland. Tomlinson responded to the various stories run by SIS about this book at

http://www.the bigbreach.com/tomlinson/statement.htm