Francis Beckett

London House, 1999, £20

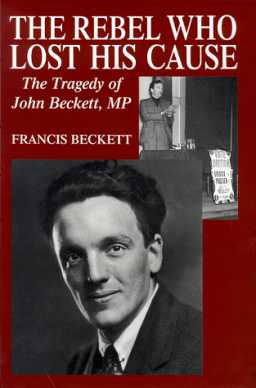

John Beckett has always been an enigma: the fiery left wing Labour MP who became one of Mosley’s fascists, an unrepentant anti-Semite and war-time internee. How to explain this trajectory? Francis Beckett’s new biography is of particular interest because it is an attempt by the man’s son, a left wing journalist (New Statesman education correspondent) and historian, to understand what his father became in the course of the 1930s.

Francis Beckett’s picture of the Labour Party in the 1920s is very reminiscent of today’s New Labour, cutting benefit and cosying up to big business. On this particular occasion, it culminated in the Labour leadership’s defection, forming a coalition government dominated by the Conservatives. John Beckett’s disgust at these developments is quite understandable. Less understandable is his ending up in the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Beckett lost his seat in the 1931 General Election and in the years that followed seems to have been looking for a new political home. He was impressed by Mussolini’s Italy, found William Joyce, one of the BUF’s star propagandists, a convincing speaker; but in the end, according to his son, he was forced to throw in his lot with Mosley through financial hardship. Mosley offered him a salaried post in the BUF. He was appointed director of publicity and successfully boosted sales of The Blackshirt from 13,000 to 23,000 and of Action from 5,000 to 26,000. To this reader, such a dramatic changing of coats suggests that his socialism had only ever been worn lightly.

The man Beckett chose to follow, Oswald Mosley, has been the subject of an attempted major rehabilitation job in the last thirty odd years. His own autobiography, My Life (1969) and Robert Skidelsky’s 1975 biography,Oswald Mosley, tried to portray him as a great constructive statesman, admittedly flawed, but certainly not a criminal; in fact, as a great wasted talent. This man, we are routinely assured, could have led either the Conservative or the Labour party; but then so could Tony Blair, so this hardly amounts to a great endorsement, even assuming its validity. But what does this biography contribute to the debate?

Beckett was never one of Mosley’s fervent devotees or uncritical admirers, but was always sceptical of the political talents, the infallibility to which the so called ‘Leader’ laid claim. His habit of referring to him as ‘the Bleeder’ can hardly have endeared him to Mosley’s inner circle. According to Francis Beckett, his father regarded Mosley as a megalomaniac (surely one of the qualifications for a fascist leader!), who was increasingly out of touch with reality. The final proof was during the abdication crisis when Mosley confidently expected Edward VIII to stage a constitutional coup, dissolving Parliament and installing him as Prime Minister. The call never came, although there were a few in Establishment circles who were worried that the King might just be desperate enough to attempt this. Despite this setback, Britain’s ‘man of destiny’ continued to regard his ascension to power as imminent, a delusion that continued even in prison in the early 1940s.

Beckett, together with William Joyce, was finally purged by Mosley in 1937. The revisionist view is that this was because of their anti-Semitic excesses: they were ideological anti-Semites but Mosley only embraced anti-Semitism in response to Jewish attacks on the BUF. This is so much nonsense. As Francis Beckett convincingly argues, they were expelled because they were critical of Mosley’s leadership, not because of their anti-Semitism. While he does not minimise the extent to which his father had become a ‘racist bigot’, he makes it quite clear that these were attitudes and opinions that he had acquired in the BUF. The terrible irony is that Beckett’s own mother was Jewish.

The politics the BUF propagated in the East End of London were the politics of the anti-Semitic pogrom. Far from being a flawed, but constructive statesman, Mosley was a failed pogromist. The Left defeated him on his chosen ground. Considerable effort has been put into disguising this. One example will suffice. His opposition to the Second World War has been seriously presented as a statesmanlike alternative to Chamberlain’s appeasement and Churchill’s warmongering. Indeed, if Mosley’s policies had been followed there would have been no war and therefore no Holocaust! The reality is that the core of Mosley’s opposition to the war was that Britain was going to war not out of self-interest but on behalf of international Jewry.

Part of the artfully constructed body of lies that Mosley contrived was that he was not and never would have been a traitor during the Second World War. His post war relations with the remnants of German Nazism and the European collaborationist movements demonstrated otherwise. Beckett provides another useful piece of evidence. While his father was interned, he was approached by one of Mosley’s entourage with an offer of reconciliation and a place in Mosley’s provisional government. When he refused, he was told he had been placed on the ‘to be shot’ list.

While certainly not the last word on John Beckett, this is an interesting account that throws some new light on Mosley, the BUF and the British Right in general. It joins a growing body of recent publications in the field. Particularly deserving of mention are Tony Kushner and Nadia Valman’s Remembering Cable Street; Dave Renton’s Fascism, Anti Fascism and Britain in the 1940s; Richard Griffiths’ Patriotism Perverted; Trevor Grundy’s Memoir of a Fascist Childhood; and John Hope’s excellent article, ‘Blackshirts, Knuckle Dusters and Lawyers’ that appeared in the Spring 2000 issue of the Labour History Review.