Kimberley Cornish

London: Arrow, 1999, £7.99

On p. 86 of this enthralling book Kimberley Cornish invites readers to complete the following sentence: ‘Wittgenstein was offered the Chair in Philosophy at Lenin’s university [Kazan] in 1935 because…’ What possible reason can there be except that he was serving the Soviet regime? Cornish contends that Wittgenstein recruited the Trinity College spies and, while recognising that the evidence he adduces does not amount to conclusive proof, he makes an overwhelming case for rejecting the assumption that it was an Englishman who persuaded Burgess, Philby and Blunt to work for the Soviet Union.

The author is an historical detective with a wide knowledge of philosophy, who excels at tracing the threads of complex cultural and political networks. When Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in 1929 his reasons for doing so were obscure, but his years at Trinity brought him into contact with the three men already mentioned, and he taught other noted Marxists: Julian Bell, Maurice Cornforth, David Haden-Guest, John Cornford and Alister Watson. Wittgenstein was taught Russian by Fania Pascal, who was probably a Comintern agent and whose husband Roy, like Wittgenstein, lodged one summer with another active Communist, Maurice Dobb. Wittgenstein and Blunt both visited the Soviet Union in the summer of 1935.

In the 1920s Wittgenstein wrote of his desire to flee to the Soviet Union, and friends recall many instances of his sympathy for Communism. Was he the mysterious ‘Fifth Man’? His political views, his friends and his students make it a distinct possibility. Only someone with a powerful charisma could have prevailed upon so many young men to commit themselves to a cause which led some of them to exile and early death.

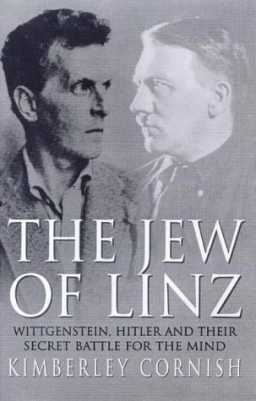

Wittgenstein had made an even more significant impression earlier in his life, if Cornish is to be believed – one which affected the course of twentieth century history. That Wittgenstein and Hitler, born within a few days of each other, attended the same school in Linz, is dismissed by Wittgenstein’s biographer Ray Monk as a mere curiosity: ‘There is no evidence that they had anything to do with each other.’ Cornish thinks this improbable, given their shared devotion to Wagner and Schopenhauer, and their forceful personalities. The young Adolf, with his artistic leanings, would have been very interested in this famous member of the Wittgenstein family, whose house in Vienna was a salon for leading cultural figures. But some incident occurred which turned their friendship into hostility. Cornish demonstrates that many instances of Hitler’s anti-Jewish rhetoric can be applied specifically to Wittgenstein and his family; and he draws attention to a curious phrase Hitler used during a speech at Linz in March 1938, ‘international seekers after truth’. When asked in the 1920s why he was anti-semitic Hitler replied that it was for ‘personal’ reasons; and Cornish notes how he planned to establish Linz, rather than Vienna, as Austria’s most important city. ‘We face the astounding possibility’, he concludes, ‘that the course of the twentieth century was radically influenced by a quarrel between two schoolboys.’

If so, the quarrel’s result was that Hitler came to loathe the Jews in general on account of what he hated about the Wittgenstein family in particular: its immense industrial power and suspect financial dealings and the undermining of the German people by its industrial policy of employing Slavs as cheap labour. The Wittgensteins were also Hitler’s enemies in the world of music, for they had adopted the virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim, whom Wagner abhorred. Hitler followed Wagner in detesting the influence of the Wittgenstein family on the Viennese musical world. Wagner’s anti-semitic tract of 1850 contains a passage which anticipates Nazi policy, considering the possibility of a ‘violent ejection of the destructive foreign element’ from German culture. The love of music which, Cornish suggests, would have brought Wittgenstein and Hitler together, turned into a prime reason for the latter’s hatred of Jews.

Perhaps the most important figure, however, is Schopenhauer, to whose writings both Hitler and Wittgenstein were devoted. Cornish suggests that Wittgenstein drew from him in a particular philosophy of the mind which Hitler appropriated and altered for his own ends. For this reviewer, one of the Cornish’s greatest achievements is to reveal the significance of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. As a philosophy student in the 1960s I was baffled by the weight my teachers attached to that book’s ‘private language’ argument, and reacted against the Wittgenstein cult. Ironically, though, unlike their master, his disciples were secularists of the analytical school and ignored his deeply mystical and religious outlook, presenting a decontextualised figure whose only links were with Russell and the Vienna Circle. There wasn’t the faintest whiff of politics, religion or music about the Wittgenstein they offered us.

The chapters dealing with Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mind are very demanding, but their essence is that, influenced by Schopenhauer, he believed in an ‘unknown Universal Mind’ and that Hitler perverted this idea into a nationalist doctrine of the Mind of the Master Race. Schopenhauer derived his mysticism from Ayran doctrines, which Nazis like Rosenberg used to build their racial theories. The idea of a racial mind lent itself to the practice of magic, and Cornish examines the role of the occult in Nazism, different theories of magic’s efficacy, and Wittgenstein’s belief that philosophy itself was a magical practice.

It is impossible to do justice to such a densely-written book in a review of this length. To read Cornish’s work is to became aware that there is a strong prima facie case for making Wittgenstein a key figure both in creating Hitler’s anti-semitism and, through the work done by his student Alan Turing at Bletchley Park, in defeating it.

More detective work on Wittgenstein’s life in Cambridge during the 1930s now seems essential. Perhaps some answers will emerge, not from Cambridge, but from the new treasure-trove of Russian archives.