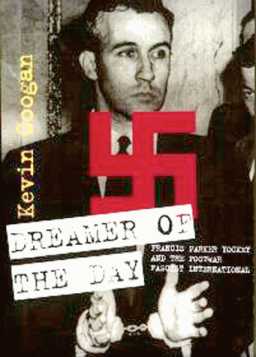

Kevin Coogan,

Autonomedia, New York, 1999. $16.95 www.autonomedia.org

When Francis Parker Yockey met his own personal Ernstfall with his typically vaudevillian suicide by cyanide pill, dressed only in his underpants and a pair of jack boots, it frustrated an eight year FBI manhunt for the ‘mystery man’. The impact of his gesture was no doubt not quite what he had intended. His death generated a modicum of local press interest but the matter swiftly faded from view, overshadowed no doubt by the emergence of his antithesis, the eminently more photogenic ‘tabloid Führer’ George Lincoln Rockwell. To all intents and purposes Yockey died as he lived, in complete obscurity; and had it not been for the timely intervention of Spotlight publisher Willis Carto who republished his Imperium in 1962, that is where he would have remained.

Given his propensity to secrecy, Yockey’s subsequent obscurity is of little surprise and it seems churlish to note that somewhere within Coogan’s 644 page tome there is a slim biography peeping through. His tendency to disappear from view is what made for such a protracted manhunt; and the book itself is a fascinating case study of how the FBI and related intelligence agencies interact to compile information and track their subject. As it is, Coogan’s biography at last centrally locates Yockey, and his importance to post-war fascism, by painstakingly retracing his footsteps through the murky world of his work for Henry Ford’s Michigan strike breakers; the German-American Bund; Nazi sabotage networks; turbulent relationships with Mosley and Gerald L.K. Smith; the post-war fascist international and its intersection with Western intelligence; KGB, Soviet diplomats; Stalinist artists; white Russians; a mysterious Hebrew school principal cum diamond smuggler; Cuban journalists; Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother; Gladio; Euro-terrorists; S & M – ‘whipping women’ – and even, if Canadian fascist Adrien Arcand is to be believed, an unsurpassed recipe for mashed potato.

The last appears to have perished with him but with this one exception Coogan, who has been mesmerised for the past fifteen or so years by Yockey, appears to have recovered much of this tale and in doing so has produced an extremely important book, a worthy successor to Kurt P. Tauber’s magisterial Beyond Eagle and Swastika, for anybody wishing to understand the course of post-war fascism in all its ‘sprawling tangle of irreconcilable positions’.(1) Indeed, the strength of his work lies not only in his erudite handling of this ‘sprawling tangle’ but in taking seriously the minutiae of the internal ideological debates that have unfolded within the far-right during the past fifty years.

Coogan’s ‘highly speculative’ central hypothesis is that the Yockey represents the (barely visible) tip of an iceberg which saw a substantial revision in fascist thought. After Stalingrad there was a qualitative shift within the SS, necessitated by strategy, away from Rosenberg’s biological exultation of Nordicism towards the ascendant pan-Europeanism of the Waffen SS and factions within the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office) who saw it as detrimental to an effective occupation policy. Embracing Nordicism as a desirable yet unattainable aesthetic ideal, this element set about restructuring fascism along a ‘softer’ and thus more acceptable ‘Italian’ line.

In conjunction with the mobilisation of Nazi financial and intelligence networks to prepare underground structures to survive Allied occupation, men like SS Colonel Franke-Grisch and Julius Evola were hastily theorising the ideological framework for the survival of what Coogan terms ‘the Order’, a resurrected Knights Templar modelled on the ‘black monks’ of the SS. This dialectic continued into the 1960s with the emergence of the pan-Europeanist Northern League which, in line with A. James Gregor, historian and secretary of the International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics, vehemently assailed the simplistic Rassenkunde (Racial Science) of Hans K Günther causing him, at least publicly, to moderate his stance and join the Northern League.(2) Though not ‘Yockeyist’, the Northern League joined him in calling for the abandonment of a crude Darwinian conception of race in favour of a brand of ‘spiritual’ or ‘cultural’ racism that has begun to percolate into many aspects of academia and New Right thought, most notably in Yockey’s spiritual heir, Alan de Benoist.

The ‘sprawling tangle’ has continued to exist within ‘the Order’; but to conceptualise this ‘East-West’ dichotomy as a rigid split is not particularly meaningful. Yockey saw the anti-Semitic show trial of Rudolf Slansky in Prague and the Soviet Union’s closed economic system as evidence that the true ‘Dostoyevskian soul’ of Russia was turning against the ‘culture distorters’ and could be used, in the same way as the liberation struggles of the Third World, to fight the ‘ethical syphilis’ engendered by the American backed NATO ‘occupation’ of Europe.

Yockey’s attempts to divine an anti-American neutralism drew the praise of Major-General J. F. C. Fuller (whose diaries show that he met Yockey in 1949). Fuller, a military historian of some note, was one of Britain’s premier theorists of mechanised warfare during the First World War. A fanatical anti-Semite whose writings were imbued with the occult as a result of his friendship with Aleister Crowley. In 1935 Fuller had been at the forefront of the moves to modernise the British Union of Fascists which he had joined in the interim. Despite his considerable military knowledge he was not recalled by the War Office in 1940; nor was he interned, despite fears that he was the most obvious candidate to ‘do a Pétain’. After the war, anxious to prevent Soviet domination of Europe, Fuller began to interest himself in the techniques of psychological and guerrilla warfare which led him into the arms of MI6 and the Anti Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) in their covert war against the USSR during the 1950s.

As Coogan notes, the methods and alliances used to divine a European Imperium may have been radically different but the ‘split’ remained ‘essentially a tactical question’. For Coogan ‘The Order’s’ penchant for Schaukelpolitik (see-saw politics) was directed at playing off Dulles’s CIA against the Soviet Bloc, wringing concessions from both, to ensure the survival of their own goals.

Outside the myopic circles of the occult and French New Right, Yockey’s curious ideas seem all but forgotten. Coogan’s study then is a timely reminder that his Imperium, far from being parenthetical was, and is, part of a wider polemic within post-war fascism that is integral to our understanding of how it seeks to resurrect itself from the ashes of the Third Reich. Such was the nature of its gyrations that Yockey could work both as a speech writer with a ‘considerable relationship’ to the viscerally anti-Communist Senator Joe McCarthy (and the network behind him which was seeking to invalidate the Nuremberg Trials), and, only months beforehand, as a courier for Czech intelligence. When he dropped off the radar between Spring 1955 and Winter 1957, Coogan believes that he may well have been acting as a coordinator between German fascist groups and the USSR. While such abstruse compacts led the FBI and the Anti Defamation League to Yockey’s door, many on the fascist fringe mistook him for a Communist.

But such Byzantine alliances had their historical antecedents in the post-war maelstrom of WWI when Germany and Russia found themselves forced into military cooperation with one another by virtue of the fact that they were both pariahs in the eyes of the Rapallo powers. The clandestine rearming of Germany, in which the Soviet Union was complicit, saw ‘Mother Russia’ repaid with the slaughter that accompanied Operation Barbarossa. Indeed the ‘conservative revolutionary’ geopolitics that made possible such alliances belies Coogan’s thesis that the today’s left is immersed in the throes of similarly deadly malaise. For those who have indulged in the recent rather worrying fascination of denying that the left had any in part to the evolution of fascist thought (let alone arming its military machine), Coogan warns that they could be condemned to repeat the mistakes of the past. ‘The left has today so deteriorated,’ he states, ‘that it may well lack the capacity for understanding, much less fighting, new forms of fascism that incorporate “leftist” rhetoric and ideas.’

Quite.

If Willis Carto and the fascist fraternity who cherish his memory have misunderstood Yockey’s ideas and the implications of their many guises, it is important that we do not.

Notes

- Roger Griffin, ‘Reviews’, European History Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3, (July, 1995), p. 479

- Launched in 1958 by Roger Pearson, the Northern League was modelled as a cultural organisation extolling the virtues of ‘Pan European Friendship’. Its rather more sophisticated approach to ‘Rassenkunde’ proved immensely popular within the far right and saw soon most groups worth their salt affiliating to its standard.Hans F.K. Gunther was a German anthropologist who wrote a series of well-received works on the topic of Nordic romanticism during the 1920s, and which from 1933 resulted in, amongst other things, the introduction of cranial measuring into German schoolrooms as part and parcel of the Nazification of German schools. Thanks to a leg-up from the Thuringian Nazi Party in 1930 Gunther was appointed to the University of Jena with his inaugural lecture being attended by Hitler himself. Through his work, which set out to prove the racial superiority of the Aryan race both theoretically and physically – he had been involved in the compulsory sterilisation programme of children born to black fathers in the Ruhr, ‘Rassen-Gunther’, as he was affectionately known, rose to become one of the SS’s most prominent ideologues. His membership of the Northern League thus provided the group with ‘a link with the heyday of the tradition’. See Marek Kohn, The Race Gallery: The Return of Racial Science (Jonathan Cape: London, 1995), p. 52.