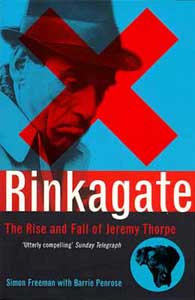

Simon Freeman and Barry Penrose

Bloomsbury, London, 1996, £16.99

Penrose was one of the co-authors of The Pencourt File and this is Pencourt revisited. But revisited by Freeman: this is his reworking of the Pencourt material.

Pencourt – Penrose and Courtiour – had been commissioned by Harold Wilson to investigate the plots against him but, unable to get to the bottom of that, they ended up doing the Thorpe/Norman Scott story. I would guess they were steered in that direction by the people they started out trying to investigate. The most interesting section of Pencourt was chapter 23 in which the authors circled round the G.K Young – Civil Assistance ‘private armies’ episode in 1974-6, in the process getting quite close to the various psy-ops operations which were then going on. Nearly twenty years later, with hindsight and the Wallace/Wright material from the 1980s, Freeman has chosen to ditch all that. In the introduction (p. 8) he describes reading The Pencourt File.

‘It defied the conventions of style and structure and was the literary equivalent of a pile of bricks at an exhibition of “modern art”, which everyone circles, puzzled, but certain that it must mean something. Eventually I gave up trying to make sense of the jumble of names and dates….’

In this new version Young, Walter Walker and all that has gone. Colin Wallace is not mentioned; Wright gets one reference in the introduction. Instead of redoing Pencourt as it had been intended in the first place, Freeman has chosen to ignore all the psy-ops material and rewrite the Jeremy Thorpe/Norman Scott story. For the second time The Pencourt File has become the story of Jeremy Thorpe and Norman Scott!

The result is not uninteresting. There is a lot of new information on Jeremy Thorpe’s years of living dangerously as one of the most prominent faces in British politics while cruising London’s gay scene. There are also more detailed accounts of a number of the episodes in Pencourt, including the moves made by the higher management at the BBC to shut them up; the Peter Bessell version of events, the perambulations of Norman Scott – and the actual conspiracy to murder him. But in ignoring the psy-ops operations Freeman has served up an interesting snack rather than a main course.

There is one absolutely wonderful comment from Wilson’s private secretary and confidante, Marcia Faulkender, on p. 388. Asked by Freeman to comment on the stories about her having had an affair with Harold Wilson, she replied:

‘Did I fancy Harold? No. He had a wonderful brain and I thought he was God. I absolutely adored him but he used to tell smutty stories and put milk bottles on the table. How could I have an affair with a man like that?’ (Emphasis added.)

Not for nothing is she Lady Faulkender.