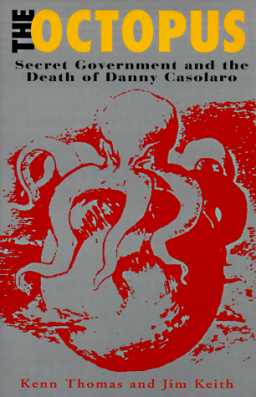

Kenn Thomas and Jim Keith

Feral House, PO Box 3466, Portland, OR 97208 (), 1996, $19.95

Of all the current parapolitical ‘biggies’ floating around, the one I would not have enjoyed trying to piece together is this one; and I am grateful to Thomas and Keith for doing so. Casolaro was, on this account, a genial, rather naive, middle class journalist and poet manqué. With some knowledge of computers, he had been turned onto the Inslaw/Promis story early by one of the creators of Promis.(1) From there, without any background in parapolitics or investigative journalism, he began poking around in some of the biggest and most dangerous stories of the past few years of American’s imperial twilight. As his investigations proliferated and he discovered the usual overlaps between the various threads he was working on – organised crime, intelligence agencies; what we might call, after Peter Dale Scott, deep politics – he began to perceive what he thought were signs of centralised control over large areas of his investigative field. He began calling this perceived control group ‘The Octopus’, and apparently thought he could trace its origins back to a group of spooks, led by James Angleton, who wanted ‘revenge for the notorious Albanian operation which had been compromised by Kim Philby’. At the rear of the book there is a Casolaro chronology in which ‘The Octopus’ is suggested as being involved in almost every major parapolitical event of the post-war US empire.

‘The Octopus’ is a decent metaphor but on the evidence presented here – and the authors have had access to Casolaro’s notes and his manuscript – Casolaro’s evidence for this central control group was thin; and for the role of Angleton and the Albanian connection non-existent. To even call this stringing together of dates and personnel an hypothesis would be straining things.

What was Casarolo investigating? Well…. this is where it gets hard to summarise, but the list, starting with the most reliable areas – solid-looking factoids – includes: the Promis soft-ware, and its alleged re-engineering and theft by sections of the Federal government; its alleged abilities to access all other systems to which it is connected; and its alleged distribution world-wide so the NSA (?) could access, via the soft-ware, other countries’ information systems; Earl Brian, who may have sold it, who may have been part of the Bush October Surprise; Michael Riconosciuto and his various allegations/fantasies; the use of the land owned by the Cabazon tribe to manufacture a number of weapons and intelligence products, launder money (or was it drugs? or both?)…… From there he spins off into BCCI, the S and L rip-offs; spook operations here there and everywhere; numerous murders and ‘suicides’.

But Casolaro’s notes show he was poking around in everything; UFOs, Area 51, Pine Gap, MJ-12, the mafia – even the Illuminati – all the signs to me of a beginner floundering around in the wonderful wacky world of American conspiracy theories, unable to tell shit from Shinola.

The authors thicken this almost indigestible dish, lobbing in – just to give one example, to show their methods – the deaths of the British journalist Jonathan Moyle in Chile, Ian Spiro, said to be working either for the CIA or MI6 – or both – and Abbie Hoffman. Moyle’s in there because he was interested, apparently, in some of the same people as Casolaro; and Spiro’s in there because, apparently, he had some contact with Casolaro just before his death. Hoffman’s in there because….well, Hoffman had written a piece about the October Surprise – and his death, the authors assert, is ‘connected to Inslaw’. But only, apparently, because Hoffman was interested in the October Surprise and one or two of the people in the Inslaw case were also – or claimed to have been – involved in the October Surprise. Robert Maxwell’s in there: he, apparently, sold bootleg versions of Promis. Confused? You ought to be; but also, maybe, fascinated. Because this is fascinating stuff; almost every page has something interesting on it, often in the footnotes.

I have two other difficulties with the book. The first is the authors’ ambiguity. Do they accept the Casolaro thesis? If not – and it is not always clear that they do – which bits don’t they buy? At the begining of the book there is a ‘note on sources’; and well there might be. For the authors have included, in the footnotes, all manner of dodgy stuff, including anonymous material, chunks from La Rouche publications, second and third-hand expansions of Casolaro’s own material and bits off the Internet. All of these are included because ‘they illuminate the research in obvious ways’. But to illuminate is not to support (or falsify). This is a stew, the authors are saying, and you can pick out the bits you want to chew on.

My second difficulty is related to the first. Take this paragraph on a page I opened at random.

‘And what of the George Bush address found in the address book of CIA agent George de Morenschildt, the control agent for Lee Harvey Oswald? DeMorenschildt had been a spy for the OSS in German intelligence, and some have speculated that he may also have been Bush’s CIA handler’.

DeMorenschildt’s role with the CIA or ‘handling’ Oswald have not been established. This version may well be true but where’s the evidence? Where’s the evidence that he was an OSS spy inside German intelligence? As for Bush’s address being in De Morenschild’s book – both men were involved in the oil industry; both men lived in Texas. It strikes me as not remotely surprising (although mildly interesting) that Bush’s address appears in De Morenschildt’s book. Finally, the idea that De Morenschildt was Bush’s ‘handler’ is invention, pure and simple. Almost every page has something screaming out for more investigation, more evidence, or more scepticism.

The authors accept that Casolaro was murdered. They reconstruct his final few days and, indeed, he did not behave much as I imagine a near-suicide behaves. But what do I know about suicides? The evidence presented here could as plausibly be reinterpreted thus: Casolaro did indeed have the outline of a big story – or, rather, of several big stories, some of which overlapped, some of which didn’t. However he had nothing like the evidence needed to write the massive book he was talking of, had failed to get a contract for said book, and was deeply – $200,000 – in debt. It is not psychologically absurd to see Casolaro concluding that he wouldn’t get the evidence and wouldn’t get the contract; and, not being able to face this, checked out.

So: interesting, full of fascinating bits and pieces, but unsatisfactory. And my proof copy didn’t have an index.

Notes

- Promis was a soft-ware package, produced by the firm Inslaw, which, it is claimed, enabled the user to keep track of an individual – say, a prisoner; or, say, a political trouble-maker – through a maze of state computer data bases.