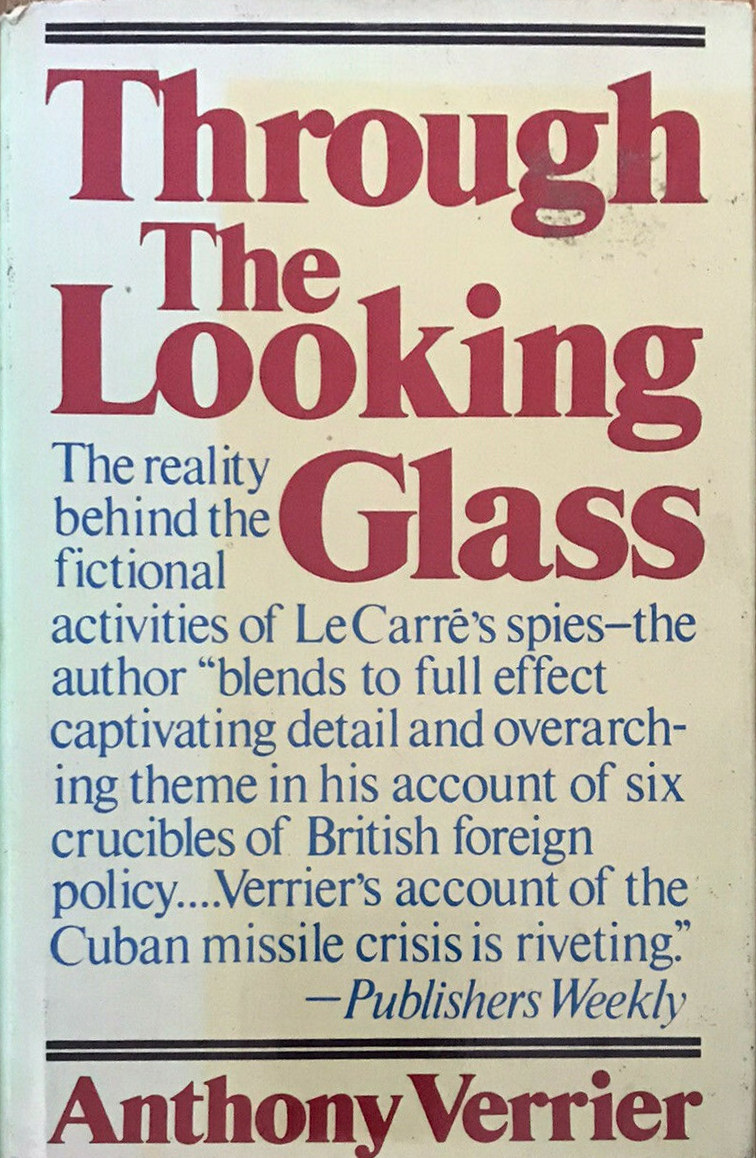

Through The Looking Glass: British Foreign Policy In An Age Of Illusions

Anthony Verrier (Cape, London 1983)

This will probably turn out to be an important book, maybe even a little landmark in the (scanty) literature on British foreign policy since the war. So far it has been largely ignored by the literary/political establishment, receiving only 4 reviews that we’re aware of – Financial Times, 5th March 1983; International Affairs, Summer 1983; Guardian 17th September 1983 and London Review of Books, 4th August 1983 – and the last of these, by David Leigh is so dismissive as to barely count as a review at all. To Mr Leigh’s curious reaction I return below.

Verrier has written a kind of expose’ of certain incidents in British foreign policy: Suez, Nigeria/Biafra, the Albanian operation of 1949, Kuwait in 1961. There is also an account of a period at the beginning of the 1970s of the war in Northern Ireland, what amounts to a revisionist history in miniature of WW2 intelligence operations on the British side, and a sardonic post-script on the Falklands:

“Mrs Thatcher postured absurdly in the immediate aftermath …an illusion about an independent almost an imperial role comparable to that which regards nuclear weapons as deterrents to every variety of threat.” (p338)

The post-war illusion that Britain remained a ‘Great Power’ despite having had to asset strip the Empire to pay for the war is one of his major themes. But, in his view, the illusion was sustained by the politicians, and not by the Civil Service – what he calls ‘the permanent government’ – and certainly not by the secret Civil Service, SIS (MI6). For Verrier’s second thesis, the one I guess he really cares about, is that SIS got it right. There it is, out front, in the final paragraph of his introduction.

“Both SIS and the Security Service..have officers with as keen a sense of realities as the most sceptical student of Britain’s recent history…One such officer, in Lagos during the Nigerian Civil War, argued for two years that the real requirement was to learn something of the state of Nigerian politics, not the activities of the KGB. There was indirect opposition to Bevin in 1949, and to Eden in 1956….In Northern Ireland, from 1971 onwards, SIS officers came to believe that the Provisional Irish Republican Army was a political organisation which could be outwitted, not merely a terrorist organisation which must be destroyed. SIS also provided adequate and timely intelligence of Argentinian intentions concerning the Falkland Islands”.

As a thesis it has its antecedents. Peter Dale Scott (and others) have demonstrated that the Pentagon Papers were systematically skewed to show the CIA in a favourable light vis a vis the Vietnam War – always right, and ignored by the politicians, the military and the foreign policy establishment who mired America in a war they (CIA) had opposed from early on. This view conveniently glosses over the Agency’s role in running covert ops (if that even begins to describe something as large as the war in Laos) in S.E. Asia. Similarly, Verrier just ignores most of the covert activities described in Bloch and Fitzgerald’s British Intelligence and Covert Action reviewed in this issue.

The Pentagon Papers may have been a CIA operation: Fletcher Prouty has long maintained this, and he was sitting at the focal point between the Agency and the Pentagon. And Verrier has certainly had an awful lot of help from SIS personnel. The book is littered with accounts of what (unnamed) SIS people did, thought and said, such statements sometimes put in (unattributed) quotation marks. At one point, for example, he quotes at length from a speech given by Dick White, then head of SIS. One wonders how he got this, and who if anyone gave permission for its use. The possibility has to be considered that the book is an SIS job. I don’t think it’s likely, but it is a possibility.

Despite an almost total lack of documentation, Verrier’s display of ‘insider’ knowledge produces a curious certainty of tone. There is no rational reason for believing (or disbelieving) most of his assertions but I found it difficult to sustain any sceptical view for long. Academics, whether they believe him or not, will never take the book seriously because there is so little documentation. Yet as a source of new hypotheses on the postwar years it must be without precedent in this country. Verrier has quietly eased the lids on a great many cans of worms. Almost every page contains sections begging to be quoted. This, for example on p42:

“Thus SOE, whether riff-raff or not, had become Churchill’s instrument for the execution of a Balkan strategy which appeared to meet all the imperial requirements and the views about Russia which he (and an increasingly quiescent Eden) shared with the Chiefs of Staff. More to the point, by mid 1943 SOE in Cairo forced its way on to the ULTRA distribution by reading what was clearly intended for others. Rough stuff became the order of the day, above all in relations between SIS and SOE”.

Or this, on p. 255:

“Macmillan’s attempt…to fight the good fight in Yemen, was tacitly opposed by SIS because, all other factors apart, it degenerated into a matter of bribes to the wrong people -£30 million to be exact, laundered through the Colonial Development and Welfare Acts.”

Two examples: the list could have been 20, and if I had more knowledge, probably 200.

David Leigh in his review in the London Review of Books, dismisses Verrier as “enfeebled by his incapacity to name names and his willingness to act as an apologist for his MI6 friends”.

This is harsh. Yes, in America, where Leigh has spent some time recently, names are named. Over the period covered by Verrier a great deal of detail of parallel American activities is available – names, who took which decisions, sitting on which committees. For the most part this isn’t true here, and books with titles like Who Makes British Foreign Policy? (James Barber), can’t ever actually answer the question. There is no information: the ‘weeders’ see to that. But this is no reason to get sniffy about what (little) there is on offer. Where the history of the British State goes, the occasional crust is always better than no bread.

Just how far we are from the American situation is beautifully if unwittingly demonstrated by James Cable’s review in International Affairs. Cable, actually Sir James Cable, ex Ambassador Cable, focuses on Verrier’s ‘startling assertion’ that Lord Normanbrook, Secretary to the Cabinet, “used SIS liaison with CIA as a means of telling the President what was really at stake,” just before Suez.

Cable is apparently shocked by this claim. Assuming his reaction to be genuine, its naivety is one good measure of another facet of the ‘looking glass world’: the comforting belief that things are more civilised in this country. That this particular assertion of Verrier’s should have to wait 28 years before getting aired says all there is to say about our ruling elites’ grip on our history. That Cable should be shocked – or should feel it worth while feigning shock – and that a journal with the public gravitas of International Affairs should find his gaucheries worth printing says a good deal about the enervated condition of academic writing on British foreign policy.

Robin Ramsay

War and Order (Researching State Structures)

edited by Celina Bledowska (Junction Books 1983)

Compiled from material presented at the Researching State Structures Conference in November 1981, it is designed to assist ‘the continuing process of discovery’ and ‘to clarify methods used’ by the respective writers. The book is divided into four areas: military, contingency planning, communications and police. Each area has a series of short articles (one or two pages) outlining present research and providing guidelines for future projects.

Some of the material is extremely useful, but overall the book is a disappointment. It is expensive; articles have appeared before; and there is no bibliography. Photocopy the bits you need.

The Investigative Researchers Handbook

compiled and edited by Stuart Christie. (Refract 1983)

Christie has produced a manual for investigating state functionaries and right-wingers rather than state structures, and as such is a companion to the above. Although it is to be recommended for the wealth of information sources provided (potentially extremely useful) it is let down by poor design, with too many blank spaces and a series of charts on investigated individuals which are not illuminating, just confusing.

Eagerly awaited is the new Refract book on the international fascist Stefano Delie Chiaie (Portrait of a Black Terrorist -£3.50 Box A, 84b Whitehall High Street, London E1 7QX). Anarchy magazine has undergone a collective sea-change and there appears to be a move away from the endless recycling of anarchy’s glorious past. The last two issues have been excellent, with hard original research on the Masons, the SAS, the World Anti-Communist League, etc. Available from the address above @ 50p plus postage.

Author Jonathan Bloch has been refused permanent residence in Britain. A South African refugee, he has lived here since 1976. Home Secretary Leon Brittan stated that Mr Bloch has “acted in a way which might be construed as inimical to the interests of the host country”. (Guardian 30th December 1983). The cause of Brittan’s displeasure is BRITISH INTELLIGENCE AND COVERT ACTION by Bloch and Patrick Fitzgerald (Junction Books 1983). An intelligence tour of the Empire, pieced together from published sources, the tale presented is of an intelligence agency, MI6, as grubby and nasty as the CIA. As per usual the book and the decision on Bloch have been received in the media and amongst the left with virtual silence. Inevitably the book ends with Ireland, the subject of Roger Faligot’s BRITAIN’S MILITARY STRATEGY IN IRELAND (The Kitson experiment) (Zed Press 1983). The book is full of episodes which deserve fuller inquiry, from the Airey Neave assassination (in next Lobster) to the Birmingham bombings. It is a devastating expose of an intelligence system out of control and outside the state system. Talk of democratic accountability from the Labour Party is a sick joke when one reads what took place when they were in power.

Both of the above have good appendices (including a long list of intelligence operatives); are choc full of information leads. Not great books – or definitive ones – just, at present, the only ones.

Secret Police

by Thomas Plate and Andrea Darvi. (Abacus Books 1983). OK, but paperbacks are becoming expensive and this one we have heard before: familiar stuff on DINA, SAVAK, spread thinly, and the material on the KGB is decidedly dicey, reads like the Reader’s Digest. What are worthwhile are the nearly 90 pages of notes and booklists, useful for research.

The Killing of Karen Silkwood

by Richard Rashke (Sphere 1983) Destined to be a Hollywood film and one fears the worst. Silkwood for me remains a pretty unsympathetic character, but of course her mysterious death was a tragedy and deserves investigation. The book is a good read with Rashke doing little more than relating other peoples’ material, which is a shame because once it gets into NSA and CIA involvement with local police forces it becomes fascinating, and provides the real reason for the cover-up. (It discloses that MI6 use Andros Island in the Caribbean along with the CIA for training.) No index.

The Puzzle Palace: America’s National Security Agency and Its Relationship with Britain’s GCHQ

by James Bamford (Sidgewick and Jackson 1983)

Now the standard work on the NSA (No Such Agency). Excellent research, though its presentation is very boring at times. Sometimes Bamford is too taken with the technology (which one has to admit is pretty amazing) at the expense of the domestic side: i.e. the break-ins, the bugging, operatives on the ground. A good piece on Prime and GCHQ (shows America has suffered far more than Britain from ‘moles’). Good notes, index.

“I don’t want to see this country ever go across the bridge. I know the capacity is there to make tyranny total in America, and we must see to it that the agency and all agencies that possess the technology operate within the law and under proper supervision, so that we never cross that abyss. That is the abyss from which there is no return”. Senator Frank Church on NSA’s Sigint technology.

Steve Dorril

Faligot’s book was withdrawn after threats of legal action but copies may still be knocking around, and it should be in the library system.