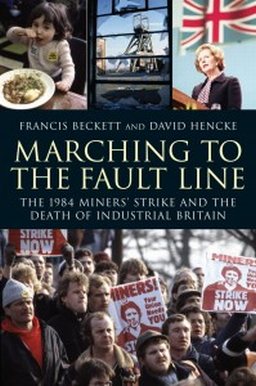

Francis Beckett and David Hencke

London: Constable, 2009, h/b, £18.99

This is quite interesting and impressive; but with a strange spin. There is a lot of (to me) new detail on the impact of the event on the Labour Party and trade unions, on money given to the NUM from other unions and on attempts to resolve the conflict. The authors show us the senior levels of the trade union movement, the National Coal Board and some politicians trying to find a way out of a fight which they saw as an expensive, unnecessary grudge match which the miners were going to lose. And they were going to lose. This was the Iron Lady (with a general election victory, the defeat of Argentina and the powers of the state) that they were up against. The NUM had not prepared much for the strike: the authors tell us they began it with outdated campaign maps left over from the 1973/4 strike and sent some of their ‘flying pickets’ to stand outside sites that had been closed.

I supported the strike until the 1974 so-called ‘Ridley plan’ (1) was revived in the media. This made it clear that the miners had been pushed into a strike for which the Thatcher wing of the Tory Party and the state had been preparing for a decade – Miners’ Strike 2, the Showdown with the Left – and thus the miners were doomed.

On page 245 of this book the authors write:

‘the Prime Minister thought she was on a crusade against an Antichrist. After vanquishing the Argentineans she was going to vanquish “the enemy within” – the name she gave to thousands of British citizens who wanted……..to be allowed to go on earning their living in the hard, dangerous productive way that their fathers and grandfathers had done.’

This is misleading; and, given who the authors are – Hencke has been reporting on the British political scene from a centre-left perspective for over 25 years and Beckett has a written a history of the Communist Party of Great Britain (2) – I do not see how this can be anything but deliberately misleading. As the authors surely know, Mrs Thatcher used the term ‘the enemy within’ to signal to the anti-subversion lobby in and attached to the British secret state, that she was fighting not ‘British citizens who wanted……to be allowed to go on earning their living’, but the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB); and behind them, their Soviet masters. Mrs Thatcher had bought the communist subversion theories of the likes of Brian Crozier.

Why did the authors decide to omit this? This is much more interesting than their version here. The 1984 miners’ strike was the climax of the anti-subversion lobby’s struggle with the ‘communist threat’ since they began getting anxious about it in the late 1960s. What makes the story so interesting, tragic and stupid, is that by the time of the strike the CPGB was almost paralysed by internal conflict (Eurocommunists versus tankies); and not only were the CPGB’s industrial department people not running the strike in secret through the NUM, as Mrs Thatcher apparently believed, the CPGB didn’t even really support it. Formally they did – how could they not? – but they could see as well as others that it was going to be a disaster.

MI5 must have known about the CPGB’s lack of enthusiasm since they had the CPGB penetrated from top to bottom. So there’s another story to be told: what kind of reports did MI5 give to the PM about the CPGB’s role in the strike? Retired MI5 director-general Stella Rimington was in charge of the MI5 operations against the miners, and said this:

‘The 1984 miners’ strike was supported by a very large number of members of the National Union of Mineworkers, but it was directed by a triumvirate who had declared that they were using the strike to try to bring down the elected government of Margaret Thatcher and it was actively supported by the Communist party. What was it legitimate for us to do about that? We quickly decided that the activities of picket lines and miners’ wives’ support groups were not our concern, even though they were of great concern to the police who had to deal with the law-and-order aspects of the strike; accusations that we were running agents or telephone interceptions to get advance warning of picket movements are wrong. We in MI5 limited our investigations to the activities of those who were using the strike for subversive purposes.’(3)

A ‘strike for subversive purposes’ legitimised MI5’s activities; and Arthur Scargill made no bones about it, seeking funding from the Soviet bloc and Colonel Gaddafi. (It was as if he was following a script written by the Conservative Central Office and MI5.) But Rimington’s statement does not quite support Thatcher’s ‘the enemy within’ theory about the CPGB. I assume that MI5 knew that her theory about the role of the CPGB in the strike was false; but MI5 didn’t need to believe it to act as they did. An industrial trade union, led by CPGB members and ex-members, opposing government policy, was more than enough. The nonsense – the communist conspiracy theory – in Mrs Thatcher’s mind was of no relevance to MI5. But it surely is relevant to this story.

Beckett and Hencke give us an expanded take on the received version on the centre-left: the miners had no choice but to strike, lost a lot of political support by not having a national ballot, and stayed out far too long pursuing a lost cause because Arthur Scargill would not admit defeat. All of which is true, in my view. It’s just a pity that the authors didn’t do justice to the role played by the anti-subversion lobby and the secret state in the affair.(4) Not least, Seamus Milne’s research in his The Enemy Within has not been taken seriously enough.

Notes

- This is not mentioned by the authors.

- Enemy Within (London: John Murray, 1995)

- In a legal sense she is probably telling the truth: GCHQ/NSA would do the intercepts and Special Branch ran the agents, as has been admitted since.

- I discuss this in my contribution to Granville Williams (ed.) Shafted: the Media, the Miners’ Strike and the Aftermath, (London: Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom, 2009).