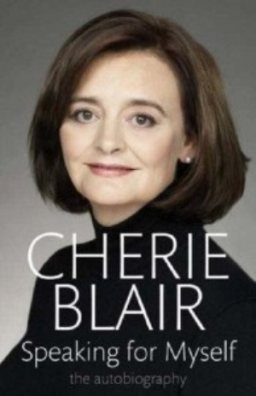

Cherie Blair: Speaking for Myself

Cherie Blair

London: Little, Brown, 2008, h/b, £18.99

The relentless harrying of Neil Kinnock by the Murdoch press at the time of the 1992 general election outraged Labour Party people, among them Cherie Blair. This was the general election when The Sun proudly boasted that it was its continual ridicule and abuse of the Labour leader that had won the election for the Tories. Indeed, Cherie’s anger was such that the Murdoch papers were banned from the Blair household. Today, her autobiography has been serialised in that very same Sun newspaper. It is not The Sun that has changed over the intervening years.

But how does her autobiography remember the 1992 general election? There is no mention of the way the Murdoch press hounded Kinnock, or of the anger this caused at the time. To dwell on such an unsavoury episode would only call into question her husband’s subsequent courting of Murdoch, pledging New Labour’s allegiance to his business interests. (1) It would also have precluded serialisation in The Sun and The Times. This is typical of the whole book: Cherie sanitises her past, deleting her Old Labour beliefs and principles in order to present herself to the world as if she has always been what she is today. While we must be careful not to exaggerate how left-wing she was, the fact remains that for her New Labour involved a journey to the right, whereas her husband was already there to begin with.

How does she remember the great class battles that were taking place when Tony Blair first became an MP? The 1984-85 Miners’ Strike gets one paragraph out of 405 pages of text. ‘It was’, she tells us, ‘a painful time.’ Even her personal hairdresser, Andre, gets more – indeed, gets considerably more – attention than the Miners’ Strike. This is all the more remarkable considering that Blair’s Sedgefield constituency was home to many miners and that one of the men who secured Blair the nomination for the seat was Gary Kirby, a miner, who was to be arrested during the strike.

Even more disgraceful is her brief mention of the 1986 Wapping strike which is, in a roundabout way, blamed on the print workers’ ‘corruption’, which she was familiar with, she tells us, through her ‘employment law work’. This is a complete travesty. The strike was deliberately provoked by Murdoch, with the full support of the Thatcher government, in order to deny the workers their redundancy payments. She must have known this at the time through, as she puts it, her ‘employment law work’, but now she chooses to parrot the Murdoch-line. Moreover, the way the strike was policed was such a scandal that it provoked a report, ‘A Case To Answer’, by the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers. Any mention of this would be just too Old Labour. And, of course, a lawyer married to an MP is hardly in a position to complain of corrupt practices in the print!

How does she deal with her abandonment of her Old Labour beliefs? She simply deletes them and, instead, presents herself very much as a domestic person, mother and wife. Indeed, the book is actually described as being about ‘a family on a journey.’ This is how she deals with the Iraq War, for example. Supporting Blair’s stand was, she writes, ‘my job as his wife’, a strange position for someone who still claims to be a feminist. On another occasion, she attacks Alastair Campbell’s partner, Fiona Millar, who was strongly opposed to the war. Fiona carried on a ‘non-stop tirade’. In the end, Cherie had to tell her that ‘if Tony tells me, as he does, that if we don’t stop Hussein the world will be a more dangerous place, then I believe him. And in my view, you and I should be supporting our men in their difficult decisions, not making it worse by nagging them.’ This is the considered justification that a top lawyer makes of the illegal invasion of Iraq and all of the horrors that have followed: she had to stand by her man!

Cherie found compensation for her lost beliefs and principles in greed, the very New Labour pursuit of personal enrichment. For someone with a huge income from the law, she developed a taste for freebies: while Blair was Prime Minister, the family enjoyed free holidays worth hundreds of thousands of pounds. On one notorious occasion in Australia she was invited to pick out a few gifts for herself when visiting a clothes store and then to the astonishment of the staff helped herself to 68 items worth £2,000. This embarrassing pursuit of freebies has less to do with her poor childhood (her excuse) than with sublimating her lost principles.

This is an attempt to present as a domestic odyssey what in reality has been a tale of blood, greed and betrayed hopes.

Notes

- See, for example, David Hencke and Rob Evans, ‘Memo shows how Blair aided Murdoch’, The Guardian, 1 November 2008.