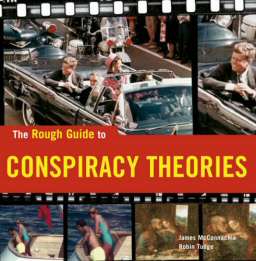

James McConnachie and Robin Tudge,

London, New York: Rough Guide Ltd (Penguin Books), 2005, p/b

£9.99 / $14.99 (US) / $22.99 (Can)

This chunky paperback is intended to give readers an introduction to the world of conspiracies and the theories around them, as opposed to works which discuss conspiracy theories as a topic in their own right. It takes over 80 topics, divided into themes such as assassinations, mega-conspiracies, religion, USA, calamities and so forth, giving an average of 4/5 pages to each, sometimes with information box-outs on related subjects. Each topic is sourced both in print media and relevant websites.

The book is remarkably up-to-date, featuring many events from 2005 and covers all the most obvious ‘conspiracies’ up to and including the disinformation surrounding the invasion of Iraq in 2003. There is a bias towards American material in the book; but the bulk of the extant material emanates from and relates to that country. One presumes that the book is intended for global sales, so it is understandable that some of the British scandals of the 60s and 70s, for example, don’t get a look in.

So far, so good: the book is a worthwhile introduction to the subject for anyone who hasn’t really done any reading in this area. There are more than enough leads to follow-up to keep happy most people who develop an interest in any particular subject.

For more seasoned campaigners however, the book has less to offer. In many of the topics, such as those covering the Calvi murder, the plots against Harold Wilson, the CIA drugs connection etc, anyone who has been following the topics will feel that some of the more obvious and important texts have not been referred to. The Wilson plot sources do not include The Pencourt File or Smear!; the chapters relating to the Calvi murder do not include the Larry Gurwin and Rupert Cornwell books; and the CIA/MK-ULTRA section omits John Marks’ classic text. Equally puzzling is the lack of any reference to Richard Sauder’s text on underground bases, or Nick Begich on HAARP. Of course one has to allow for time considerations: two authors who read all the relevant material on all the topics would never have been able to meet any publication deadline; and I expect that some titles from the 1970s and 1980s may now be more difficult to obtain easily and cheaply.

Any book such as this invites readers to construct their own wish-list of topics that really should have been included. I would probably include a wider selection of secret and security services and their misdeeds, including South Africa’s apartheid era BOSS and the French sinkers of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior; an investigation into the murky world of mineral mining in Central Africa is long overdue; Charles Higham’s Trading with the Enemy would be worth a chapter for its revelations; Frances Stonor Saunders’ work on the CIA and the cultural cold war should be in there; as should the relationship between British security forces and the paramilitaries on both sides of the sectarian divide in Northern Ireland and the attempted cover-ups and so forth.

My one gripe is more a publisher’s failing than any fault of the authors: there are numerous references to page 000 in the text where a place mark for a future page number has been left in rather than the correct page number. That’s plain sloppiness on the part of the publishers and one trusts it will be corrected in future editions. I am also not too certain about the reliability of the index. Robin Ramsay is correctly noted on page 27 but a clearly identified paragraph about his book Conspiracy Theories on page 395 is missing.

To supplement the main body of the text, there are some interesting appendices: a readers guide to general conspiracy literature (both fiction and non-fiction); a short synopsis of a selection of conspiracy movies (but not TV series); and, finally, some websites covering conspiracy theories (including those with forums for conspiracy related discussions) and conspiracy related print materials. I was pleased to see that Lobster magazine is mentioned but sadly the Fortean Times website wasn’t.

What does come through very clearly is that the book is written by two people with a genuine interest in the subject area, but who have no particular axe to grind. They have no truck with the more extreme and unpleasant theories, especially anything that is obviously anti-Semitic or racist. At the same time they refuse to believe official accounts purely on the basis of the authority of the writers of the texts. In short, this is a collection of essays that one can safely recommend to people making their initial forays into the murky waters of conspiracy literature.Even seasoned researchers may well find new angles to explore and new sources (especially amongst the websites) to investigate.