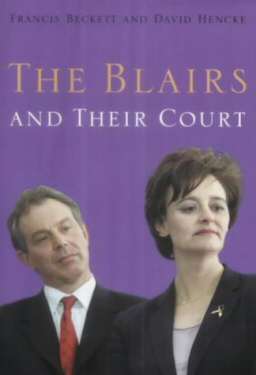

Francis Beckett and David Hencke

London: Aurum Press, 2004, £18.99, h/b

According to Beckett and Hencke, in the late 1980s Nigel Lawson could never understand why Tony Blair was a member of the Labour Party rather than of the Conservative Party. This question subsequently occurred to a growing number of Labour Party members and the answer they came up with saw tens of thousands of them becoming ex-Labour Party members. More important, of course was not why Blair himself was a member of the Labour Party but how someone so obviously a Tory was able to become party leader and moreover transform Labour into a centre right party, into another, indeed, into the main British conservative party. The ‘New’ in New Labour really meant, as one Blairite eloquently put it, ‘Not’ Labour; and this is certainly how it has turned out.

Under Blair, New Labour has embraced privatisation, the market, big business and the rich, social inequality, domestic authoritarianism, and, of course, imperial wars. Today New Labour is the real party of big business and the rich; and increasingly they fund it, staff it and run it. Alex Salmond’s unanswered question to Blair in the Commons concerning the claim that four-fifths of Labour Party funds now come from people he has either honoured or ennobled shows how things are going. How much do Beckett and Hencke contribute to explaining this historic transformation?

Their book, they proclaim, is the first biography of the great man that Downing Street refused any cooperation; and it is easy to see why. They present a devastating picture of Blair and his court that brims over with telling detail. Of particular interest to readers of Lobster is the revelation that MI6 head-hunted Charles Clarke when he was Neil Kinnock’s political adviser. It is good to know that the Home Office is in a safe pair of hands. As for Blair himself, all you really need to know about him is captured by his sneering remark, when he was Leader of the Opposition, about Frank Dobson: ‘God, we are going to have that in a Labour Cabinet’. This contempt for Dobson did not prevent Blair using him in his attempt to stop Ken Livingstone becoming Mayor of London; and, of course, Dobson’s allowing himself to be used shows that the contempt was at least partly deserved. Apparently, the infinitely gullible Dobson was promised that he would be the next High Commissioner to South Africa in reward for his participation in this unsavoury affair. He is still waiting.

Blair, Beckett and Hencke make clear, has always had a public schoolboy’s dislike of trade unions and strikes, but this has never stopped him doing deals with the union bosses. Most recently, of course, they helped him avoid discussion of the invasion of Iraq at the party conference, something that shows the state of the Labour Party better than anything.

But his career actually started with deals with the union bosses. He secured his safe seat at Sedgefield by cultivating them, most notably, Moss Evans of the TGWU, with the full support of Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock. Blair’s subsequent progress in the ‘Kinnockracy’ was apparently hindered, for a while, by Kinnock’s fear that Cherie Blair ‘was too left-wing’; and Blair himself was worried that she might be ‘a political liability. Beckett and Hencke’s discussion of Cherie Blair’s political antecedents is particularly interesting – although they seem much too kind with respect to what she has since become. They write of her hostility to the government’s human rights record and of her opposition to the invasion of Iraq; but do not take on board the extent to which she has sublimated these concerns in greed and personal enrichment. She is not, of course, alone in this. Even Neil Kinnock, whose pension arrangements would seem like a lottery win to most people, still feels the need to rake in thousands more as a lobbyist for the Baltic and International Maritime Council, now that he has ascended to a House of Lords made even more corrupt by Blair than it was before – something one would not have believed possible.

The Blairs’ love of the rich and powerful is well known. As Beckett and Hencke observe:

‘Even the most cursory study of the Blairs suggests that they are fascinated by the rich, the powerful and the famous and that they have used their position to widen their acquaintance with them. Their pursuit of such people is not very sophisticated ……………. all the evidence suggests that neither Blair nor Cherie can get enough of hobnobbing with celebrities in private.’

They attempted unsuccessfully to cultivate Prince Charles (another opponent of the war), but most telling has been their relationship with Rupert Murdoch, the patron saint of New Labour. From refusing to have The Sun in the house, Cherie Blair has been transformed into someone low enough to tell The Sun’s millions of readers that Tony is a five times-a-night man. Beckett and Hencke put Blair’s friendship with Silvio Berlusconi (he has shared a jacuzzi with the man) down to his ‘infatuation with wealth and power’. Much more likely is that he is closer politically to Berlusconi than he is to any one even in the inner circles of New Labour. Blair’s own public school education has obviously stood him in good stead when mixing with these people. His experiences as a ‘fag’ were marvellous preparation for his relationship with Rupert Murdoch and George W. Bush.

What of the Iraq War? Beckett and Hencke argue that Blair actually had a lot of influence on George W. Bush in the run up to war. The reason so many people failed to see this is because they assume that Blair was trying unsuccessfully to restrain Bush; whereas the reality was that he was wholeheartedly on the side of ‘the Washington war-mongers’.

How do they sum Blair up? They see him as a more successful Ramsay Macdonald because whereas Macdonald’s ‘lurch to the right’ led to him leaving the Labour Party, Blair succeeded in taking the Labour Party with him. To be fair to Macdonald, he had actually been a Labourite, while no one can really accuse Blair of that: he was always a cuckoo in the nest. What is astonishing is the way that the Labour Party has rolled over for the Blairites. It seems that anything is possible. Who would have thought, for example, that a member of Opus Dei could become Secretary of State for Education without so much as a murmur from the massed ranks of what must be the most pathetic assemblage of MPs in the party’s history.

Where Beckett and Hencke are least successful is in actually explaining what has happened. The Blairites are a symptom, not a cause. To understand the shift to the right in British politics we have to look to the shift in the balance of class forces in British society accomplished by Thatcher and consolidated by Blair. The rich and powerful have more influence in British society and over British politics today than at any time since the end of the nineteenth century. This is certainly not to romanticise the more recent past or to have any illusions about the performance of previous Labour governments, but we have to recognise an historically significant shift in the balance of power in our society away from the middle and working class and towards the ruling class. No government can hope to successfully hold office that does not recognise this fact – at least that is the conclusion drawn by the leaderships of all the three main parties. This is New Labour’s raison d’etre. They have changed the Labour Party from a party that tried to mediate between the ruling class and the organised working class into a party openly and unashamedly committed to the aggrandisement of big business and the rich. Even the government’s increased expenditure has been delivered in a way that prioritises the interests of big business. Gordon Brown’s great contribution to New Labour has been the private finance initiative, turning government expenditure into a bonanza for business. If one wants one policy commitment that New Labour has stuck to through thick and thin, no matter what, it is their commitment not to increase the taxes of the rich. This tells us everything about New Labour and British politics today.