Nicholas Davies

Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh, 1999, £14.99

It is by now clear to everyone, except the hard-line Unionists hankering after the restoration of a Protestant Ascendancy, that the Provisional IRA was defeated in its war against the British. Their defeat was certainly not total, so that no return to ‘the good old days’ of Stormont was possible and they have received significant concessions, but nevertheless it is still a defeat. The Provisional republicans have not only given up their military campaign to bring about a united Ireland but have actually entered a Northern Ireland Assembly and joined a Northern Ireland government. They are in coalition with not just the SDLP, but with David Trimble’s UUP and even Ian Paisley’s DUP! Even ten years ago such an outcome would have been regarded as unthinkable, as treason to the cause, as a terrible betrayal of the martyrs of ‘the thirty years war’. This is a great historic turn for Irish republicanism, amounting to the abandonment of principles that were once held to be sacred and beyond compromise.

What makes this defeat bearable, indeed what makes it possible to portray it as a victory, is the fact that the peace settlement has had to be imposed on the Unionists. The reality is that the settlement agreed with the British is unacceptable to many, perhaps most, Protestants, for whom anything short of the restoration of a Protestant Ascendancy is a betrayal. The war party in Northern Ireland today is made up not by the marginalised dissident republicans, but by the far more dangerous hard-line bigots in Paisley’s DUP, in the Orange Order and in Trimble’s UUP. They want the overthrow of the agreement and all out war. This is not going to happen, although one should not underestimate the support for the stance among sections of the Protestant population. The Good Friday Agreement has not yet been securely consolidated in place.

What factors brought about the Provisional IRA’s historic turn, their recognition that military victory was impossible? There can be little doubt that one factor was the improved performance of the security forces, in particular of the intelligence and surveillance arms. So effective had they become that the journalist, Jack Holland, could write, with only slight exaggeration, that in the 1990s the safest thing to be in Northern Ireland was a member of the security forces. The Provisional IRA was unable to prosecute an effective campaign against the British because it would have exposed them to a level of casualties that they could not sustain. This was the reality of the war in the early 1990s.

Of equal importance was the rising level of loyalist attacks on the Catholic population in general and the republican movement in particular. From the time of the Anglo- Irish Agreement of 1985 loyalist paramilitaries had been stepping up their campaign of sectarian assassination. By 1992, they were accounting for a majority of the killings in Northern Ireland. Retaliatory action by the IRA only made the situation worse with the prospect of more and more people being killed and maimed in both communities at no cost to the British. There can be little doubt that this was an important factor in the Provisional leadership’s decision to end the conflict.

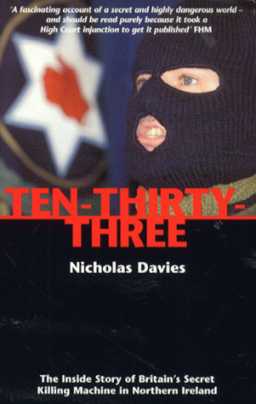

It was confidently believed at the time that British covert agencies were implicated in the loyalist campaign and the Brian Nelson case provided concrete evidence for this. Nick Davies’s new book, Ten Thirty Three, explores the Nelson affair and raises issues that must not be allowed to rest. While it is absolutely clear that the loyalist campaign was a great help to the British, Davies goes further. He argues that the murder gangs were actually being directed by British intelligence; in effect, the British were carrying out a campaign of assassination by proxy.

Nelson, a member of the UDA, presented himself to the British intelligence apparatus at the end of 1985. He was put to work as agent ‘ten thirty three’ by the covert Force Research Unit (FRU) and, over a period of time, became the means whereby the loyalist paramilitaries were brought to play their part in the British counter-insurgency strategy. There was, Davies argues, a conspiracy between Military Intelligence and the Ulster Defence Association which carried the battle on the streets to the very heart of the Republican movement; and the campaign of intimidation and killing of Sinn Fein/IRA politicians, gunmen, bombers, supporters and sympathisers by the UDA, aided and abetted by British Military Intelligence, was known about by MI5, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and a few senior government ministers and civil servants (p. 160).

There is no ‘smoking gun’ in the form of a document authorising British co-operation with the loyalist murder gangs. Instead, there is a failure to put a stop to a practice that was known about, but never acknowledged.

According to Davies, Nelson’s FRU minders provided him with detailed intelligence about republican activists, including addresses, movements and photographs. They provided him with a computer and with computer training, helping him establish a database that by the end of 1987 contained some sixty senior republicans. Having wound up their assassins, they then stood by while they carried out their work. To eliminate any risk to the loyalist gunmen carrying out the attacks, exclusion zones were imposed in those areas where attacks were to be carried out, keeping the RUC and the Army away. In time this would establish beyond any doubt the degree of collusion that Davies suggests. Moreover, the paperwork linking exclusion zones with sectarian assassinations is almost certain to still exist. We shall return to this point.

A series of brutal killings were carried out by the UDA with the assistance of the FRU. On 15 January 1988, Billy Kane was shot dead (‘the UDA had carried out the execution and once again it had been with the help and co-operation of the Force Research Unit and Brian Nelson’ p.105). On 25 July 1988 Brendan Davidson was shot dead (‘Brian Nelson, the UDA hierarchy and the FRU personnel who had helped organise the operation were jubilant’ p.113). On 23 September 1988 Gerard Slane was shot dead (‘a totally successful operation between British Intelligence and the gunmen of the Ulster Defence Association, with Nelson as go-between’ p.102). Even more dramatic was FRU involvement in actually planning the unsuccessful attempt to kill Sinn Fein councillor, Alex Maskey in July 1987. To help the gunmen escape the FRU put ‘an exclusion zone in operation on the estate where Maskey lived’ (pp. 85-86).

What of Pat Finucane, shot dead on 12 February 1989? According to Davies, Nelson told his minders of plans to shoot the solicitor and although they made clear their disapproval, they did nothing to prevent the attack. There is evidence that other sections of the security services were actively inciting the loyalists to kill Finucane; and, of course, Douglas Hogg, then a junior Home Office minister, had publicly fingered solicitors sympathetic to republicanism. More successful was FRU disapproval of UDA plans to assassinate Gerry Adams.

In the end, what brought Nelson down was the RUC Special Branch’s investigation into the loyalist murder gangs. They established a link between loyalist attacks and the imposition of exclusion zones. The operation was wound up with Nelson being sacrificed. The best estimate is that he had been involved in fifteen killings and as many unsuccessful attacks. For this he was sentenced to ten years in January 1992 and released two and a half years later, with a new identity.

Davies’s book raises very important issues at the centre of British operations in Ireland. Just as the Blair government has conceded a fresh inquiry into Bloody Sunday so we must demand an inquiry into official collusion with the loyalist murder squads. Of course, when examining cases like the Nelson case you confront two responses. The first is to deny the whole thing as paranoia, as conspiracy theory run mad. The second, as the evidence becomes overwhelming, is the ‘well what did you expect’ responses. This is big boys’ rules; this is how covert operations are carried out; this is how dirty wars are fought. Only the naive could have ever believed otherwise. In many ways, the second response is even more dangerous than the first. This is the phase we are moving into with regard to revelations about the conduct of the security forces in Northern Ireland. It is being taken out of politics and relegated to history. This must not be allowed. Those responsible for orchestrating sectarian murder must be called to account.