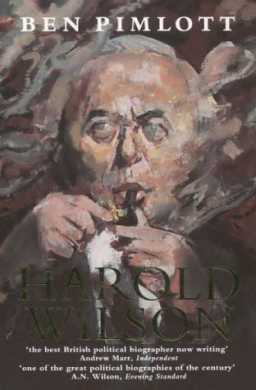

Ben Pimlott

Harper Collins, London 1992, £20

At one level, this deserves the plaudits it has received. It is a belting good read, such a good read, in fact, that I had got as far as 1967 before I realized that there was no mention of Lord Cromer, the Governor of the Bank of England between 1964 and 66, and the Labour government’s number one enemy in that period. Hang on a minute, I thought, and consulted the index. No entry for Cromer. Back to the text I went. No, not a word. R.W. Johnson described this omission as ‘a pity’ in his review of Pimlott in London Review of Books (3 December 1992). That, I guess, is academic politeness. Wilson’s account of the struggle with Cromer is the dominant theme of pp. 59-66 of his The Labour Government 1964-70 (Penguin, 1974), and Cromer is also indexed at pp. 171, 173-4, 227, 325, 562. Missing out the Governor of the Bank of England in an account of Wilson’s first administration is just seriously weird. Or perverse.

Alerted by this omission, I began paying more attention to the book and noticed that it contains almost no sense of the extra-Parliamentary forces lined up against Wilson’s governments. As a result some of Pimlott’s decisions end up looking very odd indeed. For example:

- the Industrial Reorganisation Corporation gets a paragraph but George Brown’s resignation gets 5 pages.

- There is nothing on Wilson’s financial deal with the U.S. against the City of London (and its mouthpiece, Lord Cromer).

- There is the most cursory account of the Cecil King plot.

- In key incidents like the seamen’s strike and the D-Notice Affair the received version is treated as unproblematic.

- The extraordinary period between the elections of 1974 is skimmed over in a couple of pages — private armies, rumours of coups and Heathrow manoeuvres, are all missing.

And so on.

There is a chapter on the ‘Wilson plots’ material — the Wright, Wallace story. There is a choice here. Either: it is splendid that an important, main-line political biographer like Pimlott includes such a chapter. Or: though Pimlott cites many of the main texts, he hasn’t really dealt with it adequately. The result is a bit of mess, a half-hearted ‘OK, yes, something was going on but…’ version which will be satisfactory to nobody.

I still get from Pimlott a reluctance to believe it was really as bad as that, not in dear old Britain, not in the sixties and seventies. But Pimlott is a former Labour Party parliamentary candidate. Is it simply the politician’s reluctance to acknowledge encroachment of extra-parliamentary forces, especially the British secret state, on the turf marked ‘parliamentary politics’?